You are here

Summary of CBO Update on Budget and Economic Outlook

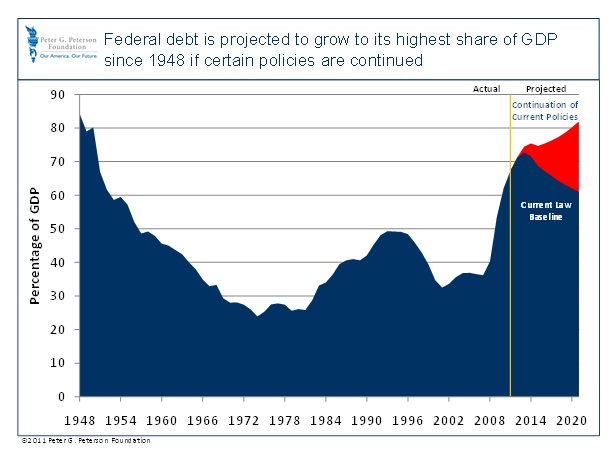

The latest report by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) on the outlook for the U.S. budget and economy highlights the costs of the ongoing weakness in our economy and uncertain direction of our nation’s fiscal policies (1). On the economy, CBO projects that a full recovery from the recession will not be complete until 2017—almost a decade after it started in December 2007. On the budget, CBO warns that if current policies are continued, federal debt is on an “explosive path” over the long run. Without changes in current policies, CBO projects that debt over the next couple of decades will “skyrocket” to levels that will harm economic growth, raise the risk of another sudden financial crisis, and cause interest rates to shoot up.

The CBO report updates the budget’s outlook through 2021 by reflecting economic, legislative and other changes to the baseline that have occurred since March. CBO estimates that the recently enacted Budget Control Act (BCA) produced the largest change by reducing deficits over in the 2012 - 2021 period by $2.1 trillion. As a result of all changes, CBO projects that debt held by the public under current law will decline from 67 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2011 to 61 percent of GDP in 2021.

However, CBO cautions that its current-law baseline understates future federal deficits and debt because the baseline assumes that spending and revenues strictly follow current law. Those assumptions are at odds with current policies. For example, the income tax provisions that were enacted during the Bush administration and extended in 2010 are scheduled to expire in December 2012, but they have been routinely extended in the past. If lawmakers extend the tax cuts and waive the Medicare payment cuts (as they have every year since 2003), they would add nearly $5 trillion to the debt over the next 10 years, easily erasing the $2.1 trillion in deficit reduction projected as a result of the BCA.

In its report, CBO also prepared an alternative fiscal scenario that assumes the continuation of popular tax policies and current Medicare payment rates. Under that scenario, federal debt would exceed 80 percent of GDP in 2021, reaching its highest level since 1948. In the years beyond 2021, CBO projects that federal debt would grow to unsupportable levels that could substantially harm the economy.

NOTE: The projected debt with the continuation of certain policies is based on several assumptions: first, that most of the provisions of the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 (Public Law 111-312) that originally were enacted in 2001, 2003, 2009, and 2010 do not expire on December 31, 2012, but instead continue; second, that the alternative minimum tax is indexed for inflation after 2011; and third, that Medicare’s payment rates for physicians are held constant at their 2011 level. The measure of debt used in these projections is "federal debt held by the public," which is the best measure for assessing the impact of government borrowing on financial markets.

CBO’s Economic Outlook

The new CBO report paints a dismal picture for the U.S. economy. The economy “remains in a severe slump” and will not recover from that slump for several years. The unemployment rate does not drop below 8 percent until 2014 and does not reach 5.2 percent until 2017. In other words, CBO projects that the economy will not fully recover for at least another 5 years, which means that the United States is facing almost a decade of lost growth since the recession began in December 2007.

Although CBO anticipates that the economy will continue to grow this year, growth will be modest, averaging only 2.3 percent. Moreover, CBO warns that its projection for growth was finalized in early July before the recent spate of bad economic news caused financial markets to tumble. If those economic developments had been incorporated into its forecast, CBO would have tempered its near-term outlook for the economy even more.

In the current environment of high unemployment and excess capacity, CBO does not see an inflation threat. Although the inflation rate picked up earlier this year (largely from a sharp rise in oil prices), CBO anticipates that inflation will ease later this year and remain low for an extended period. Under CBO’s projection, inflation drops from 2.4% in 2011 to 1.3% in 2012 and 2013 (2). This rate is below the 2% rate that the Federal Reserve says is consistent with its mandate for price stability.

CBO’s projection of the economy is consistent with the experience of other countries that have suffered a significant financial crisis. Recoveries from such crises are typically very slow. Households curb their consumption while they rebuild their wealth; banks reduce their supply of loans as they shore up their capital base; and businesses hunker down until they are confident that there is sufficient demand for their products. Indeed, these painful adjustments vividly highlight the costs of relying on growth fueled by excessive debt, leverage, and speculation, as we did before the crisis.

CBO is required to prepare its economic forecast under the assumption that current laws are maintained. Under those assumptions, CBO notes that federal fiscal policy will “provide decreasing support for the economy and thereby restrain economic growth over the next couple of years.” That restraint reflects the winding down of the 2009 stimulus, the expiration of various provisions of the 2010 Tax Act, and the passage of this summer’s deficit reduction legislation.

Many observers, however, expect that policymakers will extend some or all of the provisions of the 2010 Tax Act, which would temporarily boost growth. For example, if those and other expiring policies were continued, economic growth in 2013 could increase from 1.5 percent to between 2.0 percent and 3.5 percent. However, those effects would dissipate over time and, by 2021, real GDP would actually be lower than it would be under the current-law baseline, because the higher deficits under those policies would reduce or “crowd out” investment in new business plants and equipment. Moreover, there are other ways to stimulate the economy in the short run?such as extending unemployment benefits and reducing the employer portion of the payroll tax?that have a higher bang-for-the-buck than extending general income tax cuts, according to CBO (3).

CBO’s Budget Outlook

CBO’s report highlights the tremendous uncertainty about future fiscal policy. All forecasts are uncertain, but the current CBO forecast is especially so. The Budget Control Act of 2011 does not specify how its deficit savings would be fully achieved, and policymakers have not yet determined how they will handle upcoming expiration of popular tax cuts and other policies. These decisions will fundamentally determine the future path of deficits and debt.

Impact of the Budget Control Act

On August 2, the Congress passed and the president signed the BCA into law. The major provisions of the BCA include:

- Procedures to increase the statutory debt ceiling

- Caps on discretionary spending for 2012 through 2021

- Creation of a new Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction (which has become known as the “Super Committee”) charged with proposing $1.5 trillion in additional deficit reduction

- An automatic enforcement mechanism to achieve $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction if the Super Committee’s efforts are not enacted or do not achieve such savings

- A requirement that Congress vote on a balanced budget amendment to the Constitution.

The BCA sets spending limits and deficit reduction targets, but does not specify the policies that would be needed to achieve those goals. Although CBO was able to estimate how much the BCA would affect overall deficits and debt, it could not completely allocate the deficit savings from the BCA into specific spending and revenue projections. For example, the agency did not have any basis for determining how the Super Committee would allocate the $1.5 trillion of deficit savings among various spending programs and revenue provisions.

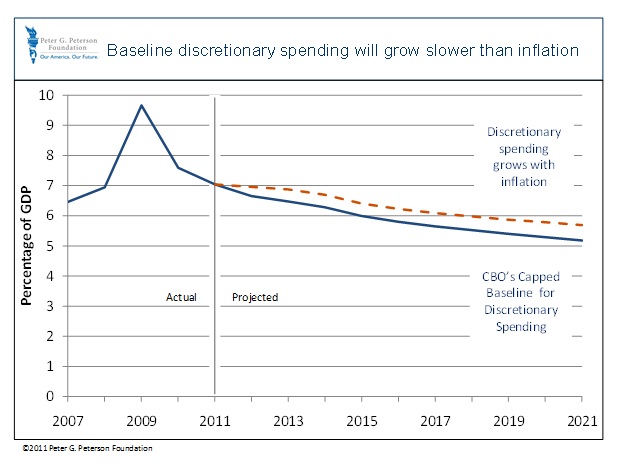

However, due to the statutory caps, CBO was able to project that discretionary spending would grow at a much slower rate than it has in recent years. CBO estimates that annual growth in discretionary outlays will average at 1.2 percent in 2013 - 2021 compared to an annual growth rate of 8 percent for 2000 to 2009 and 8.9 percent in 2010.

SOURCE: Data from the Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update, August 2011. Compiled by PGPF.

NOTE: Projections do not reflect any policy changes that may arise from the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction.

The biggest shortcoming of the BCA is that it does not explicitly address the main drivers of our long-term structural deficits. Those deficits soar because spending on entitlement programs for the elderly (Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid) grows faster than revenues do. Discretionary programs, which are the focus of the BCA, contribute little to the long-run growth of our deficits. Indeed, discretionary spending accounts for only 38 percent of the budget in 2011 and 27 percent of the budget in 2021. Thus, to address our long-term structural deficits, policymakers will have to make changes to elderly entitlement programs, revenues or both.

SOURCE: Data from the Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update, August, 2011. Compiled by PGPF.

NOTE: Projections do not reflect any policy changes that may arise from the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction.

Impact of Continuing Current Policies

CBO cautions that its baseline understates the potential growth of the debt. In developing its baseline, CBO is required to assume that spending and revenues are consistent with current laws. For example, the projections assume that:

Income tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 and extended in 2010 expire as scheduled at the end of calendar year 2012;

Medicare payments to physicians would be cut by 30 percent in January 2012 and by more thereafter, as required by current law;

Funding for operations in Iraq and Afghanistan would continue at the current, inflation-adjusted level;

The Budget Control Act would be fully implemented with caps on discretionary spending and an additional $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction from unspecified sources through 2021; and

No additional action would be taken to stimulate the economy or meet unanticipated emergencies or threats to national security

Some of those assumptions are at odds with recent practices. For example, policymakers have routinely avoided making scheduled cuts in Medicare payments to physicians and have not allowed the tax cuts to expire on prior occasions. The CBO illustrates an alternative fiscal scenario that assumes the continuation of popular tax policies and the implementation of a “doc fix” that would prevent a 30 percent cut in Medicare payments to physicians. In this scenario, federal debt would exceed 80 percent of GDP in 2021, reaching its highest level since 1948 when measured as a share of overall economic activity.

If these policies are continued, the additional deficits would add up to $5 trillion over 10 years and easily erase the $2.1 trillion in deficit reduction projected from the BCA.

The Long-Term Budget Outlook

Although the budget outlook has improved modestly with the passage of the BCA, the United States continues to face serious long-term structural deficits. Continuing current policies would put federal debt on an “explosive path” that would substantially harm the economy.

While CBO cautions that immediate increases in revenues or reductions in spending would slow the economic recovery, the agency highlights the benefits of developing a plan now to reduce the structural deficit when the economy is stronger. CBO concludes that “the sooner that medium- and long-term changes to spending and revenues are agreed upon—and the sooner they are implemented after a period of economic weakness—the smaller will be the damage to the economy from rising federal debt.”

Conclusion

According to CBO’s latest projections, the BCA represents a modest improvement in the fiscal outlook. However, many major policy decisions have yet to be resolved. Absent agreement on changes to revenues and federal programs, the BCA’s deficit reduction targets may prove to be elusive.

Demonstrating fiscal responsibility need not hamper the current delicate recovery. The way to navigate between fiscal discipline and the fragile recovery is simple—agree on a long-term plan now, with measures that go into effect when the economy is on sounder footing.

The Super Committee faces a unique opportunity to forge a bipartisan agreement on fiscal policies that can be sustained over the long-term. By agreeing on a grand bargain that solves our structural deficits in a way that also promotes job creation in the short-term, the committee could reduce the uncertainty about our nation’s future that has unsettled markets so much in recent weeks.

There are many policy options to choose from, as the recent work by the Gang of Six, the National Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform, and others demonstrates. What is needed is the political will to enact a long-term comprehensive plan. Failure to do so will further undermine financial market confidence and therefore only delay the country’s ability to get back on the right track.

(1) Congressional Budget Office, The Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update (August 2011)

(2) Inflation is measured using the price index for personal consumption expenditures from fourth-quarter to fourth-quarter.

(3) Congressional Budget Office, The Economic Outlook and Fiscal Policy Choices (September 2010).