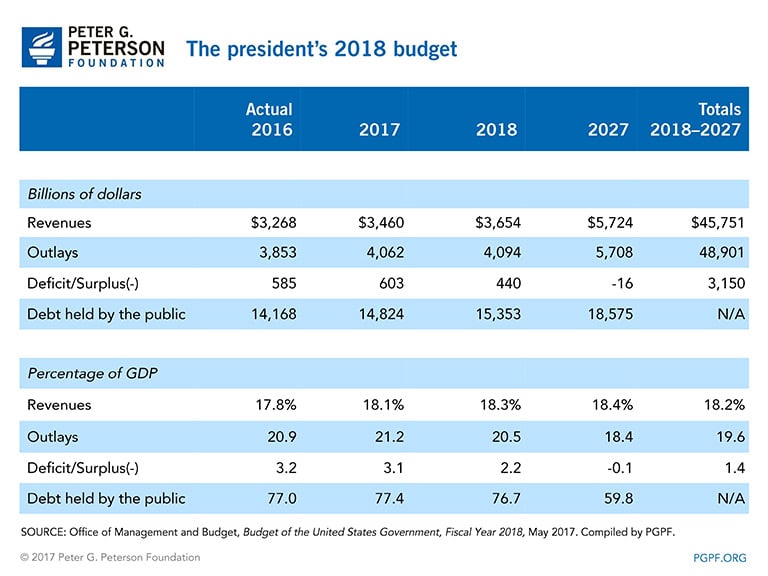

This week, President Trump released his first budget, outlining the administration’s policy proposals, budgetary projections, and economic forecasts for the next decade. The budget aims to reduce the deficit — over ten years, the budget outlines a path to reach balance and reduce our federal debt as a share of the economy. However, the budget relies on optimistic economic assumptions and does not include the reforms to the tax code that have been outlined by the administration.

Under the president’s budget:

- Budget deficits are reduced by $3.6 trillion over 10 years, and the budget is assumed to be balanced by 2027.

- Revenues are assumed to increase from 18.1% of GDP in 2017 to 18.4% in 2027.

- Spending is projected to fall from 21.2% of GDP in 2017 to 18.4% in 2027.

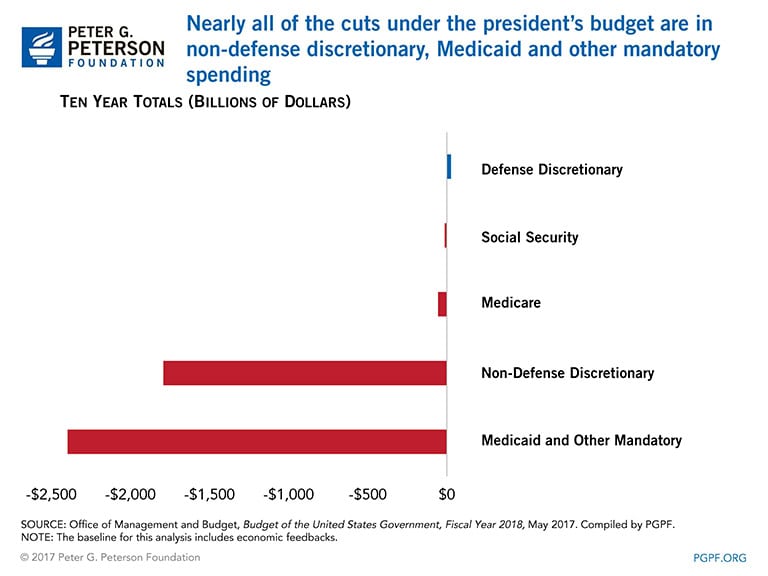

- More than 50% of the spending cuts come from reductions in mandatory programs, many of which benefit low- and middle-income families and individuals.

- Most of the rest of the spending cuts — almost 40% — come from reductions in non-defense discretionary spending.

- Spending on Social Security and Medicare will account for over 50% of the budget by 2027.

- Debt as a share of the economy is reduced over 10 years, from 77.0% today to 59.8% in 2027.

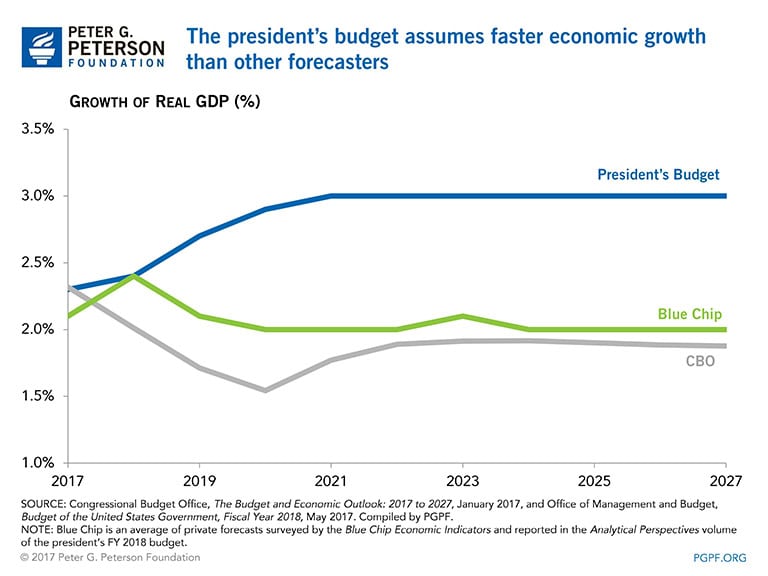

While the administration’s budget has the worthy goal of decreasing our debt levels, key questions remain unanswered. The budget relies on optimistic economic assumptions, projecting significantly higher growth rates than many other economists and forecasters. If these growth assumptions do not materialize, the budget deficit could be $500 billion in 2027 instead of reaching balance, and deficits would total $2.1 trillion more than the administration projects over 10 years.

Moreover, the president has released a blueprint for a substantial reduction in individual and corporate tax rates, yet the budget does not include those reforms or specify how they would be paid for. If those reforms are not revenue neutral, the budget deficit could be substantially higher than what is projected in the budget.

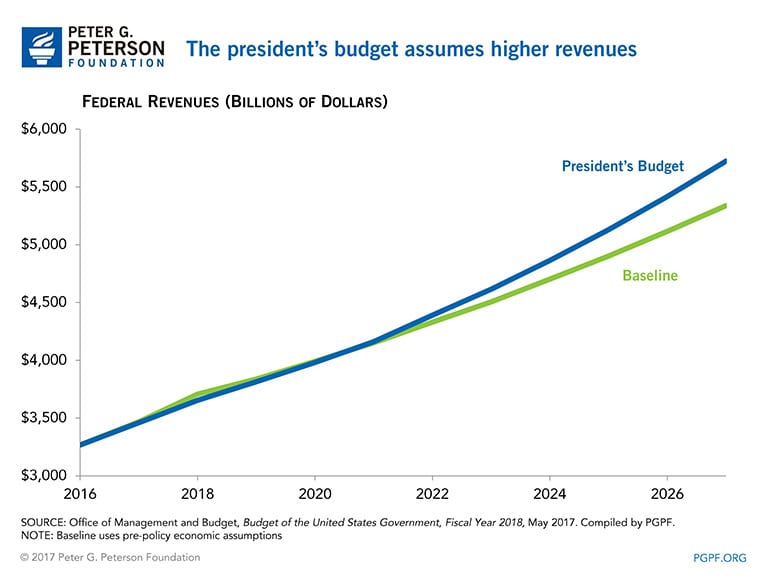

Revenues rise largely because of assumptions of faster economic growth

The president’s budget assumes that revenues will climb from $3.5 trillion in 2017 to $5.7 trillion in 2027. Over the next 10 years, revenues under the president’s budget are assumed to be $1.2 trillion higher than under the administration’s current law baseline.

The increase in revenues stem largely from an increase in economic growth.1 The administration assumes that real GDP will grow by a sustained 3.0% each year after 2020, which is substantially higher than the forecasts by other credible organizations. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that that GDP will grow at 1.9% after 2021, while Federal Reserve officials project that GDP will grow between 1.6% and 2.2% in the longer run. The Office of Management and Budget also reports that the Blue Chip survey of private forecasters expects real GDP growth to be approximately 2.0% after 2020.

Demographics will be an inevitable drag on growth

Demographics are one of the main reasons that most other forecasters expect relatively modest growth. From the 1960s through the 1990s, economic growth was boosted by baby boomers and women entering the workforce. However, baby boomers are now beginning to retire — at the rate of 10,000 per day — and the growth of women’s participation in the labor market has leveled off.

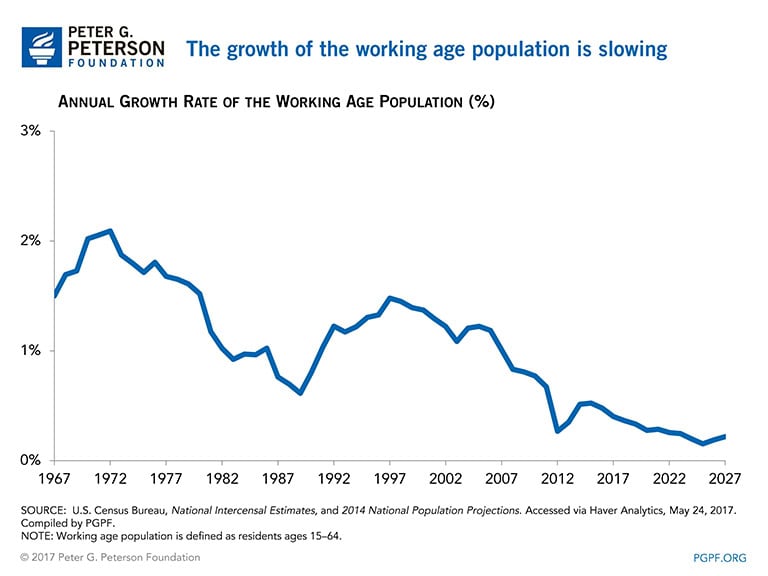

The administration did not provide information on the growth of the workforce assumed in its budget, but long-run projections of the working-age population can provide an important perspective of the way that demographics will constrain our economy in the years ahead. Over the 1960s and 1970s, the working-age population grew 1.7% each year on average. But that growth slowed to just 0.6% over the past 10 years and is expected to grow only 0.3% over the next 10 years, according to the U.S. Census.

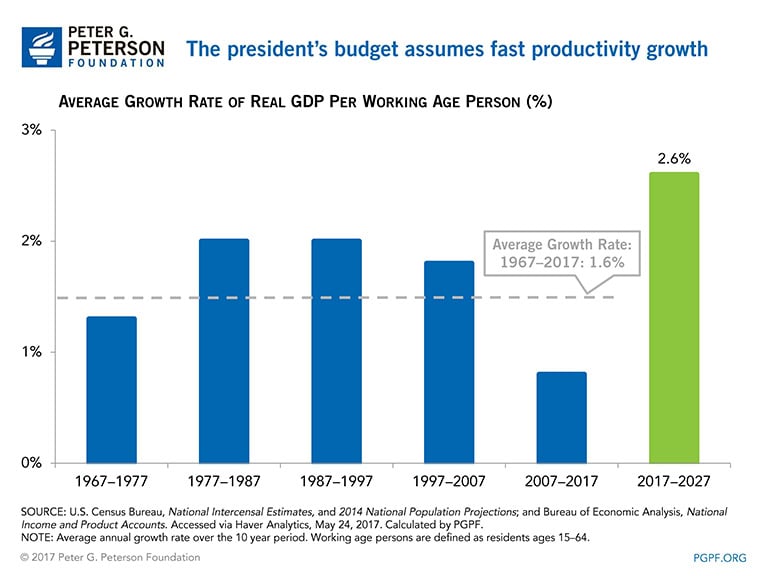

As a result of this slowdown, it will be hard to achieve levels of growth that we experienced in earlier decades without achieving very fast growth in productivity. One way to measure productivity in the president’s budget is to look at real GDP per working-age person. Using this measure, the administration assumes that productivity will grow at 2.6% per year on average over the next 10 years. That growth is 1 percentage point above the average growth of productivity over the past 50 years.

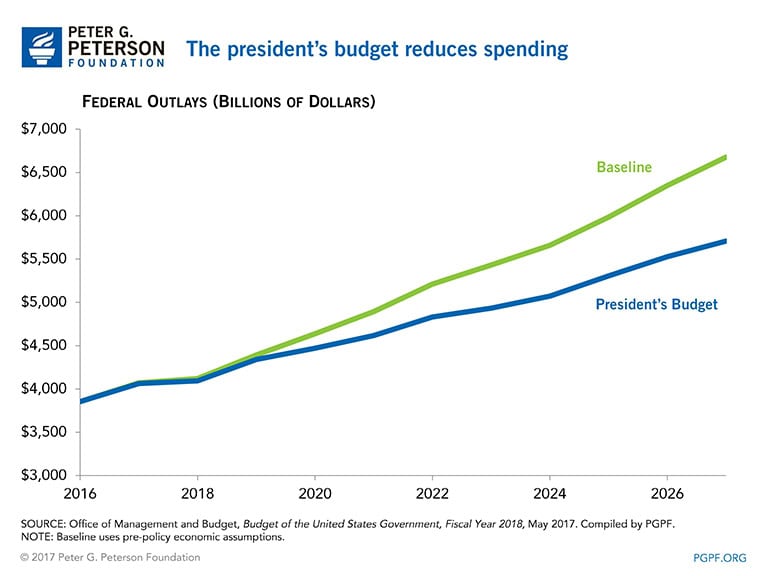

The President’s budget recommends sharp spending reductions

Over the next 10 years, spending under the president’s budget is projected to be $4.5 trillion less than under the administration’s baseline. More than 50% of the reductions stem from spending cuts to mandatory programs, while almost 40% stem from cuts to non-defense discretionary spending. Defense spending is modestly increased from baseline levels.

Discretionary Spending is significantly reduced

The president’s budget recommends cutting non-defense discretionary spending by $1.8 trillion over the next 10 years. Non-defense discretionary programs fund a variety of general government activities including scientific and medical research, education, infrastructure, national parks, law enforcement, grants to state and local governments, and pay for federal workers, among others. Defense discretionary spending is increased by $27 billion over the 10-year period.

Under the president’s budget, spending on research and development, education, and non-defense infrastructure is projected to be 1.7% of GDP in 2018, which is approximately 30% below its 50-year average of 2.6%. Federal spending on research and development alone will be only 0.6% of GDP or 40% below its 50-year historical average.

Action is urgently needed on our nation’s long-term fiscal challenges

The President's budget lays the groundwork for a much needed debate about our fiscal policies and future economy. This budget has a worthy goal of deficit reduction. However the economic assumptions underlying the president’s budget are optimistic and deficits could therefore be substantially higher than the administration projects. Important details about the president’s tax reform proposal are also unknown, and they could also have significant effects on our fiscal outlook. In addition, the budget makes large reductions in many programs that benefit low- and moderate-income families and reduces funding for some important public investments in our future.

The budget also does not address the key drivers of our long-run spending: Social Security and Medicare. Our nation’s most significant long-term fiscal challenges stem from America’s aging demographics and rising healthcare costs. We must reform and preserve these key programs soon to ensure they are sustainable for the next generation of retirees. By not reforming these high growth programs, the president’s budget relies on even more significant cuts to other programs.

In order to be politically viable and lasting, a successful fiscal plan must achieve bipartisan support. The president and Congress should work together and across party lines to find common ground in order to achieve durable policy solutions for the long-term fiscal health of the nation.

1. Although the budget contains some increases in user fees, the identifiable fees account for only 2% of the $1.2 trillion increase in revenues from baseline.

Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images

Further Reading

Should We Eliminate the Social Security Tax Cap?

There have been a number of proposals to increase, eliminate, or otherwise adjust the payroll tax cap as a way to shore up Social Security’s finances.

No Taxes on Tips Will Drive Deficits Higher

Here’s how this new, temporary deduction will affect federal revenues, budget deficits, and tax equity.

Three Reasons Why Assuming Sustained 3% Growth is a Budget Gimmick

GDP growth of 3 percent is significantly higher than independent, nonpartisan estimates and historically difficult to achieve.