Medicare is an essential federal program that provides health insurance to millions of older Americans. Because of the aging of the population and rapid growth in healthcare costs, enrollment and spending on the program have skyrocketed since its inception almost 60 years ago. One component of Medicare is the Hospital Insurance (HI) program, which covers expenditures for healthcare services related to hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, home health, and hospice care. That program is funded by taxes and other inflows to its trust fund, which is at risk of becoming depleted by 2031. Upon depletion, HI payments to providers would be reduced by 11 percent, which could affect services provided to 77 million enrollees at that time.

To ensure the sustainability of the Medicare HI Trust Fund, policymakers could enact reforms that would increase revenues for the program, reduce its spending, or a combination of both. Here we examine the changes that would reduce the program’s spending.

How Are Benefits Covered Under Medicare Part A?

The HI program, also known as Part A of Medicare, is primarily financed by a 2.9 percent payroll tax, half paid by the employer and the other half by the employee. Unlike other parts of Medicare, the HI program does not rely on premiums as a main source of revenues. In fact, most Medicare Part A beneficiaries do not pay a premium for their hospital insurance. However, beneficiaries do pay a deductible and copayments, depending on what services are used. There is no yearly limit on those out-of-pocket costs in Medicare Part A and Part B (Supplementary Medical Insurance), which is why a majority of Medicare beneficiaries have some form of additional coverage — either Medigap or Medicare Supplement insurance purchased by beneficiaries, employer retiree coverage, or Medicaid-provided cost-sharing assistance for those who qualify. Notably, Medicare Advantage (MA), also known as Medicare Part C, covers more than half of the Medicare-eligible population and is a type of insurance plan offered by a private company that contracts with Medicare to cover services included in Part A (hospital care), Part B (physician services and other medical care), and typically includes Part D (prescription drugs) of Medicare in addition to some extra benefits. Unlike traditional Medicare, MA has an annual out-of-pocket cost cap. Payments to MA plans for Part A benefits are also covered by the HI Trust Fund.

Why Is the HI Trust Fund at Risk?

Expenses under the HI Trust Fund have been outpacing its revenues due to factors such as rising healthcare costs and aging of the population — putting pressure on the financial sustainability of the trust fund. Over the past 10 years, for example, the gap between the expenditures and income of Medicare Part A was $24 billion; over the next decade, that gap is projected to climb to $333 billion. Spending has grown due to increased utilization of health services, especially as the population ages, and prices for health services typically outpace inflation. At the same time, there are fewer workers per Medicare beneficiary to help raise sufficient revenues. Unless lawmakers take action to shore up the HI Trust Fund, the trust fund will only be able to make payments equal to incoming receipts when depleted.

What Policy Options Exist to Reduce Medicare Spending?

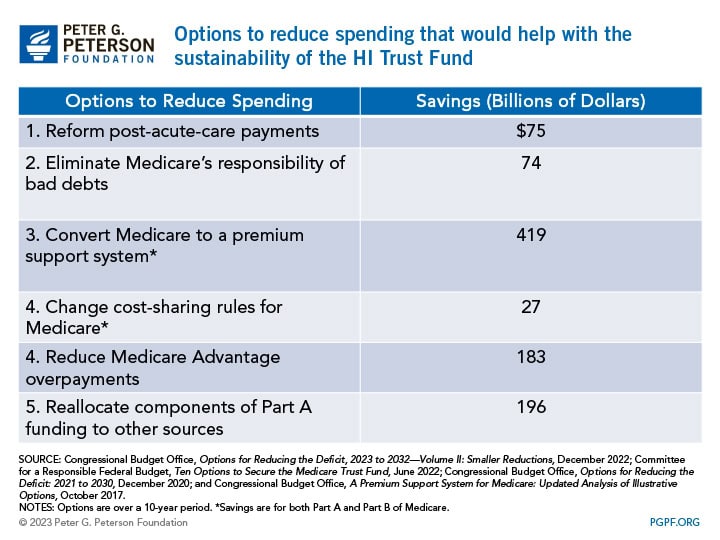

There are different approaches to reduce Medicare spending, and any reform option that would reduce Part A costs would help extend the longevity of the HI Trust Fund.

Policy Option 1: Reducing Payments to Medicare Providers

One way the HI Trust Fund could see savings is if payments made to Medicare providers were reduced. Reforming post-acute care (PAC) payments to Medicare and reducing Medicare’s responsibility for bad debts have been proposed in plans by both President Obama and President Trump to generate savings for the HI trust fund.

Reform Post-Acute Care Payments

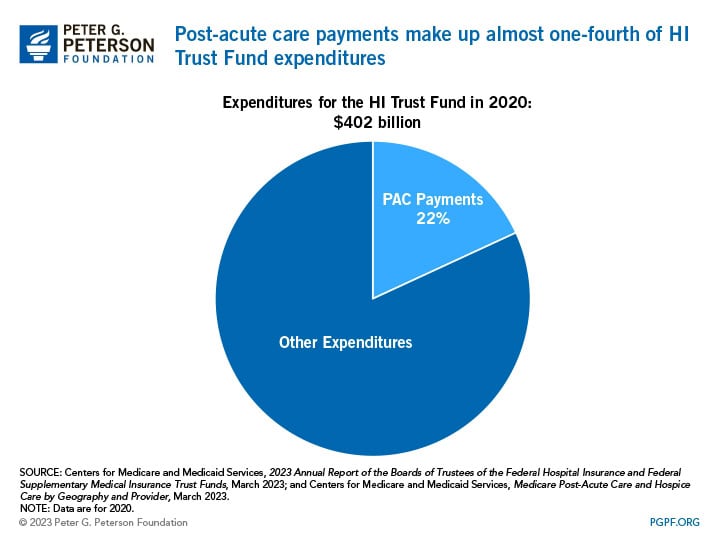

PAC, which refers to the medical services that support a patient’s continued recovery after a visit to the hospital, accounts for almost one-fourth of the HI Trust Fund’s expenditures. It includes rehabilitation and palliative services that beneficiaries can receive in four settings: long-term care hospitals, inpatient rehabilitation facilities, skilled nursing facilities, and home health agencies. Some argue that Medicare’s current system for PAC payments leads to cost discrepancies because of different payments systems that use various units of payments and adjustments. Reducing and reforming Medicare’s PAC payments could save around $75 billion over 10 years according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB).

Those in favor of reducing and reforming PAC payments argue that it would make healthcare costs more reasonable while also reducing costs under the HI trust fund. For example, Medicare payments to certain PAC providers often exceed the cost of their services because of their payment structure, leading to profits that some analysts deem as excessive. In fact, payments to PAC providers (other than long-term care hospitals) exceeded Medicare’s costs to treat beneficiaries by 10 to 15 percent over the 2008–2018 period; payments in 2020 exceeded costs by 15 to 20 percent. PAC spending also varies substantially based on location, and there is limited evidence that such spending variation is linked to different healthcare outcomes. Reforming PAC payments could help reduce some of those cost discrepancies.

Other analyses suggest that policymakers should be careful about reforming PAC payments. A study by RAND researchers found that quality of care for patients in a skilled nursing facility declined between 2000 and 2004 due to payment changes. To combat any negative externalities from changes in PAC payments, the Medicare Payment Advisory Committee (MedPAC) advises that CMS would need the authority to rebase payments so that they remain aligned with the cost of care. Swift response to the way providers react to changes in PAC payments would be necessary because over- and underpayment could threaten quality of care and beneficiary access.

Absolve Medicare’s Responsibility for Bad Debts

When Medicare beneficiaries cannot make their out-of-pocket payments for hospital services, the federal government takes on some of that responsibility. Coming from the HI Trust Fund, Medicare pays 65 percent of that “bad debt,” which would otherwise fall to hospitals and providers. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that eliminating Medicare’s responsibility to pay for such debt could save $74 billion over 10 years, while reducing the percentage of the program’s coverage of bad debt would save a smaller amount.

Proponents of this option cite that the original intent of Medicare paying medical debt was to prevent the outstanding balances of Medicare beneficiaries from being passed on to non-Medicare beneficiaries. However, because more people are now covered by some form of insurance after enactment of the Affordable Care Act, uncompensated care at medical facilities has declined — even in rural areas — and there is less need for the federal government to subsidize providers. Another way analysts suggest reducing Medicare’s coverage of bad debt is to include additional provisions for hospitals to claim bad debt, like specifying the length of time and reasonable collection efforts providers must follow before writing off a balance as bad debt.

Opponents of this option point out consequences that would impact hospitals if Medicare were to reduce or cease paying hospitals’ unpaid bills. The biggest issue with absolving the program’s debt responsibility is that hospitals would then be solely responsible for the unpaid funds. With nearly 1 in 10 American adults owing significant medical debt and rising hospital care expenditures, the increased financial burden on hospitals could be substantial. That lost source of revenue from Medicare might result in efforts by impacted hospitals to eliminate programs or services, reduce charity care, decrease staff and their salaries, and re-examine debt collection strategies.

Policy Option 2: Modernize the Payment Structure for Medicare

While the next two options would change the way payments are made across Medicare Part A, Part B, and Medicare Advantage (MA), some of the savings would go to the HI Trust Fund. The first reform option would fundamentally change the structure of Medicare, and the second option would affect MA payments for diagnostic coding, which captures the way treatments are classified and later used to determine payment rates.

Convert Medicare to a Premium Support Plan

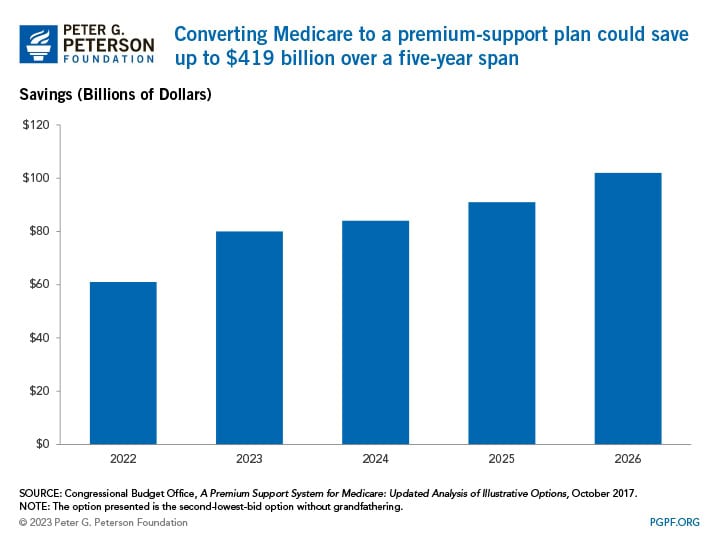

The largest policy option explored here is to make Medicare a premium-support plan. Currently, Medicare is its own form of health insurance where fee-for-service (FFS) payments are used, meaning providers receive payments based on the costs tied to specific services beneficiaries use. A premium-support plan would differ in that the federal government would provide each Medicare beneficiary with a payment to purchase their own health insurance plan and share the cost of the premiums, acting like a voucher. Payment for services would also change from FFS to capitated, meaning providers would receive an upfront amount of money based on the predicted costs of Medicare beneficiaries. While premium-support models can differ based on various policy parameters, a 2017 analysis by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) found that up to $419 billion could be saved across Parts A and B of Medicare over a five-year span if that change was implemented.

A benefit of that option is it would increase competition among plans, which would incentivize plans to keep premiums low and restrain cost growth over time. In fact, CBO found that the new Medicare premium structure could reduce net federal spending for both Medicare and affected beneficiaries by a combined 15 percent relative to current law at that time.

A consequence of this option is that it may increase costs for beneficiaries. CBO finds the premium support model noted above could increase payments made by beneficiaries, which includes premiums and out-of-pocket spending for copayments, coinsurance, and deductibles, by 18 percent. There also could be wide variation in costs depending on what program beneficiaries decide to enroll in. For example, people who choose to remain in Medicare’s fee-for-service program would generally face much higher premiums compared to current law. That would most likely happen through adverse selection — less healthy and more costly people would enroll in traditional Medicare whereas healthier and less costly people would choose a private health insurance plan. To compensate for the higher-cost enrollees, Medicare would have to increase premiums.

Change Cost-Sharing Rules for Medicare

A different approach to modernize the payment structure for Medicare is to implement cost-sharing rules between Part A and Part B. In 2023, Medicare enrollees are responsible for a $1,600 deductible for Part A services; Part B enrollees face a minimum $164.90 monthly premium, a $226 deductible, and a 20 percent coinsurance rate for Part B. Combining the deductibles for Part A and Part B into one $850 deductible, establishing a uniform coinsurance rate of 20 percent for all spending above that deductible, and implementing an annual out-of-pocket maximum of $8,500 could save $27 billion over a 10-year span.

Those in favor of this policy option find that it could decrease FFS spending for most enrollees. The Part B premium is currently linked to the growth in costs of benefits, so a combined premium would grow more slowly than under current law because Part A is expected to grow less rapidly than Part B over time. Linking Part A and Part B costs together would also simplify the program because having a single point of contact when seeking help with Medicare costs would reduce confusion for beneficiaries. Furthermore, providers may be more inclined to improve coordination between Part A and B services because their reimbursement would be lumped together, thereby reducing overall healthcare costs.

Critique of this policy centers around the financing issues that this option poses. Part A of Medicare is financed by the HI Trust Fund, but Part B is financed by the Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) Trust Fund, which relies on the government’s general fund and premiums from participants rather than on payroll taxes (which is how the HI Trust Fund is primarily funded). If cost-sharing rules were implemented, policymakers would need to consider how they want to restructure the trust funds because Part B enrollment is voluntary, meaning it does not make sense to have payroll taxes support both Parts A and B. Additionally, there is evidence that cost-sharing still results in a substantial difference between who pays what costs. Near-poor beneficiaries reported that they had difficulty affording care, whereas more wealthy beneficiaries were able to enroll in some type of supplemental coverage to reduce their healthcare costs.

Reduce Medicare Advantage Payments

Another option is to reduce Medicare Advantage (MA) payments. Specifically, the option calls for adjusting payments to MA plans to fully account for the difference in diagnostic coding patterns between MA and Medicare FFS payments. Diagnostic codes are recorded by healthcare providers to indicate a patient’s condition and subsequent treatment; they are also used to calculate patients’ risk scores, which measure the expected costs associated with a person’s care and help determine reimbursement rates. MA diagnostic coding patterns have been found to be more extensive compared to FFS. To account for that difference, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implemented a minimum coding intensity adjustment in 2018 and reduced MA plan payments by 5.9 percent across-the-board, which is also the current reduction rate for 2023. If CMS were to adjust payments beyond that 5.9 percent statutory minimum, it could reduce Medicare spending by $355 billion over 10 years by CRFB’s estimates — $183 billion of which would accrue to the HI trust fund.

Proponents of this reform option believe it is warranted because MA risk scores have grown considerably compared to FFS risk scores, and it was found that most of the increase in MA measured risk is due to differential coding between MA and FFS. Currently, MA plans respond to the payment model-induced incentive to find and report as many diagnoses that can be supported by a patient’s medical record in order to maximize risk scores and reimbursement. FFS billing increasingly includes similar incentives as more physicians and hospitals are compensated based on patient acuity, but the coding practice differences between MA and FFS remain a place where material savings for the government could materialize with a policy change.

The biggest downside of implementing this plan is that finding the appropriate adjustment amount is complex. There is not yet consensus among the healthcare policy community about the best way to measure differential coding and what an appropriate adjustment would be, especially because a larger across-the-board cut to MA payments could result in too large of an adjustment for some contracts and too small of one for others.

Policy Option 3: Shifting Costs Out of the HI Trust Fund

Another way to alleviate some financial burden on the HI Trust Fund is to adjust what components are covered by the trust fund. Shifting the responsibility of home health and graduate medical education (GME) to other financers would not reduce overall healthcare costs, but they would extend the trust fund’s longevity.

Reallocate Segments of Part A Funding to Other Sources

Reallocating HI Trust Fund-financed programs to other entities would reduce the financial burden of the HI Trust Fund. One option proposes to shift funding for GME, which allocates funds to hospitals for residents and interns, from Medicare to a single grant program financed by the Treasury’s general fund. Doing that would save the HI Trust Fund $190 billion over 10 years. Another option would be to shift home health benefits to Part B of Medicare, which is an optional part of Medicare that covers doctors’ services, outpatient care, and other medical services Part A does not cover. Doing so could move nearly $6 billion away from the HI Trust Fund’s responsibility since Part B is funded by premiums and not the HI Trust Fund.

Those in favor of making the GME program under the purview of the Treasury Department believe it would help address professional shortages and educational priorities because the Secretary could distribute amounts based on the proportion of residents in training in priority specialties or programs. That could modernize GME funding to make it more targeted, transparent, accountable, and sustainable. Proponents of shifting home health believe it is a logical move from Medicare Part A to Part B since home health is a type of outpatient care, and Part B covers such care. It would align the benefits and services that are explicitly linked by program requirements.

However, a central argument against both of those options is that they do not reduce healthcare costs — they only shift the burden away from the trust fund to another party. If Medicare were to rescind its funding from the programs, income taxes or other revenues might need to be raised in order to provide the necessary funds to finance the programs. Specifically, Part B premiums are set at one-quarter of the program’s cost, so premiums would have to increase to compensate for new costs if home health was covered by Part B.

Conclusion

As Medicare costs continue to rise, securing the HI Trust Fund is critical. Without action and reform, the trust fund could become depleted in just eight years. Reducing spending on Medicare is just one approach to helping the HI Trust Fund, but lawmakers could also consider options to increase revenues or use a combination of both. Regardless of what tools policymakers utilize, taking steps to sustain the trust fund is necessary to ensure the financial stability of Medicare and continue to provide health insurance for millions of Americans.

Image credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

Further Reading

U.S. Healthcare System Ranks Seventh Worldwide — Innovative but Fiscally Unsustainable

Spending on healthcare in the United States has far outpaced other major healthcare systems without yielding better outcomes.

Medicare’s Hospital Insurance Trust Fund Could Be Exhausted In 8 Years

Without reform, Medicare spending will continue to rise over the coming years — threatening the HI Trust Fund and placing immense pressure on the federal budget.

How Do States Pay for Medicaid?

Medicaid’s role in state budgets is unique, since the program acts as both an expenditure and the largest source of federal support in state budgets.