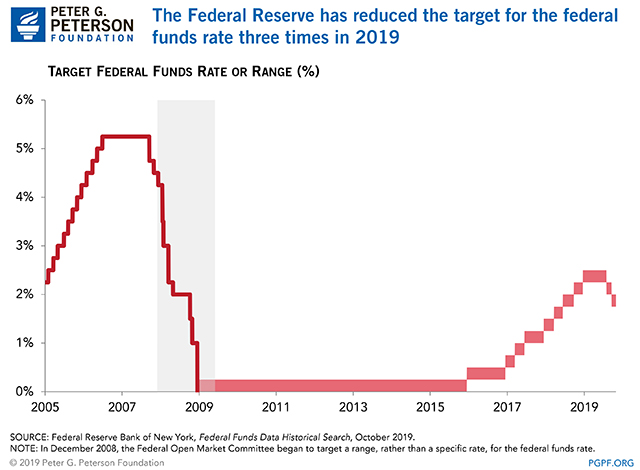

Yesterday, the Federal Reserve announced another decrease in the target for the federal funds rate — the interest rate at which commercial banks lend to each other overnight — to between 1.5 and 1.75 percent. This quarter point drop is the third reduction this year; the previous two reductions, in July and September, also lowered the rate by a quarter point each. This year’s reductions reflect the central bank’s attempts to “help keep the U.S. economy strong in the face of global developments and to provide some insurance against ongoing risks.”

The Federal Reserve uses monetary policy to achieve its statutory mandate, which is to foster maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. Setting the target for the federal funds rate is therefore an important tool for the bank because that rate is the benchmark for Treasury bills and other short-term interest rates. Market expectations about those short-term rates, combined with other factors, affect the longer-term rates that are applied to business investment loans and consumer borrowing for mortgages or car loans.

For 7 years after the financial crisis that began in 2008, the Federal Reserve held the federal funds rate close to zero to help the economy recover. It began increasing that target rate in December 2015; there were eight subsequent increases — the most recent one occurring in December 2018.

The loosening of monetary policy indicates an acknowledgement that while the economy and labor markets are strong and inflation is near the bank’s target, risks remain. The rate reduction is a support for the ongoing growth of the economy. As the press release from the Federal Reserve stated, their decision “supports the Committee’s view that sustained expansion of economic activity, strong labor market conditions, and inflation near the Committee’s symmetric 2 percent objective are the most likely outcomes, but uncertainties about this outlook remain.”

Lower interest rates are generally good news for new borrowers. However, given the size of the federal deficit — which totaled nearly $1 trillion in 2019 — the amount of borrowing by the Treasury will offset potential near-term savings from the lower rates. It is clear that even with rates low, rising debt will lead interest costs to become a larger and larger part of the federal budget.

Image credit: Getty Images

Further Reading

The Fed Held Its Target Range After Reducing the Short-Term Rate Three Meetings in a Row

High interest rates on U.S. Treasury securities increase the federal government’s borrowing costs.

What’s the Difference Between the Trade Deficit and Budget Deficit?

The terms “budget deficit” and “trade deficit” can be conflated, but they are distinct measurements of important fiscal and economic concepts.

What Types of Securities Does the Treasury Issue?

Learn about the different types of Treasury securities issued to the public as well as trends in interest rates and maturity terms.