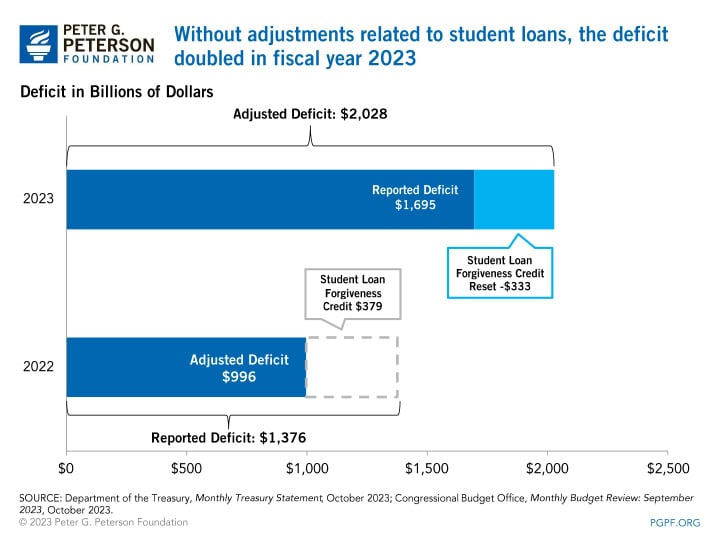

In fiscal year 2023 (FY23), which ended on September 30, 2023, the federal government officially incurred a budget deficit of $1.7 trillion — about $320 billion higher than last year's amount. However, another revealing way to examine the year-over-year change is to examine the underlying deficit, excluding one-time, unusual accounting effects resulting from a Supreme Court decision striking down the Administration’s initiative for student debt forgiveness. Looking behind the numbers in that way, we see that the underlying deficit in 2023 doubled from the year prior — a huge jump during a time of economic expansion and reflective of the country’s unsustainable fiscal outlook.

A Breakdown of the Underlying Deficit

Understanding the underlying deficit for the past couple of years requires a review of a series of accounting adjustments for the federal budget. In FY22, the Department of the Treasury recorded a deficit of nearly $1.4 trillion for the year; that total included a “cost” of $379 billion to account for the Administration’s plan for student loan forgiveness. Without that adjustment, the deficit for FY22 would have been around $1 trillion.

However, in July 2023, the Supreme Court struck down the plan for debt forgiveness; as a result, a $333 billion reduction in spending was recorded (the amount of the reduction was less than the amount of cost recorded the previous year because the cost of other provisions in FY23 offset a portion of the reduction). Without that adjustment, the deficit for FY23 would have totaled around $2 trillion.

Therefore, by excluding those unusual accounting effects, the underlying deficit doubled from approximately $1 trillion to $2 trillion — a significant increase during a time of economic growth. That $1 trillion increase in the deficit was driven by lower collections of individual income taxes and a drop in remittances from the Federal Reserve along with higher interest payments, Social Security spending, and other factors.

Why Federal Revenues Were Down in Fiscal Year 2023

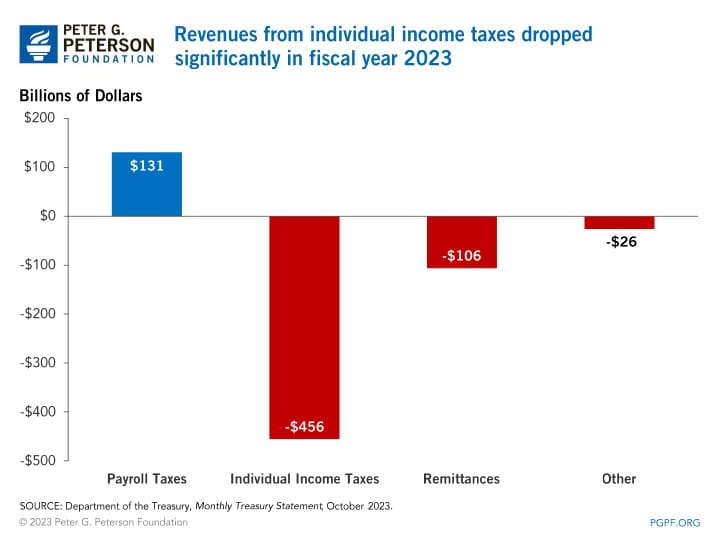

The government brought in $457 billion less in revenues (a 9 percent decrease) last fiscal year compared to FY22. That change primarily came from a $456 billion decrease (17 percent) in collections of individual income taxes despite economic growth. Lower capital gains realizations in 2022, more Employee Retention Credit claims (a refundable tax credit for employers to retain employees during the pandemic), and delayed payments for taxpayers affected by natural disasters explain most of the year-over-year decrease, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget. Further contributing to the decrease in revenues collected were smaller remittances from the Federal Reserve to the Treasury. An increase in collections of payroll taxes offset a portion of the decrease in revenues in other categories.

Drivers of Federal Spending in 2023

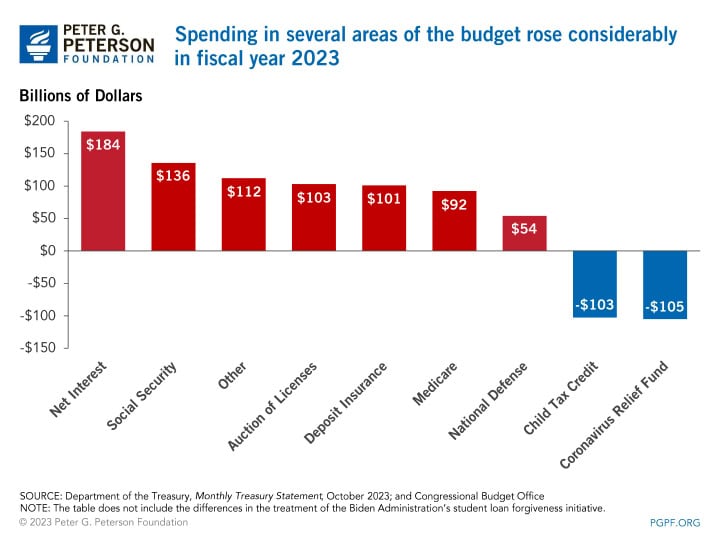

Excluding the effects of student loan adjustments, outlays in FY23 were $6.5 trillion — $575 billion higher than last year’s total (an increase of 10 percent). The main driver of the growth in outlays was an increase of $184 billion in net interest costs (39 percent), primarily due to higher interest rates. Other categories that saw significant growth in outlays were Social Security ($136 billion), deposit insurance, and Medicare. In addition, a reduction in receipts from the auction of licenses to use the electromagnetic spectrum (which are recorded as offsets to spending) increased outlays by $103 billion.

Partially offsetting that growth in outlays were the continued expiration of various COVID-19 relief measures; in particular, the spending from the Coronavirus Relief Fund decreased by $105 billion and the expanded Child Tax Credit and other refundable tax credits fell by $103 billion.

Conclusion

Excluding the offsetting accounting effects of the student debt forgiveness plan, the adjusted deficit doubled from $996 billion in FY22 to more than $2 trillion in FY23 despite a healthy economy over the same period. Annual deficits will likely exceed $2 trillion in the next decade and remain so indefinitely, if current laws stay the same. While accounting quirks may have made our fiscal health look better than it is, we shouldn’t be under any illusion about the need to reform. As the United States enters the new fiscal year, policymakers should focus on making progress on the structural issues that threaten our nation’s economic strength and preparedness in the years to come.

Image credit: Photo by Chris Somodevilla/Getty Images

Further Reading

What Is the National Debt Costing Us?

Programs that millions of Americans depend on and care about may be feeling a squeeze from interest costs on our high and rising national debt.

Interest Costs on the National Debt Are Reaching All-Time Highs

The most recent CBO projections confirm once again that America’s fiscal outlook is on an unsustainable path — increasingly driven by higher interest costs.

New Report: National Debt Outlook Gets Worse as Interest Costs Exceed $1 Trillion Annually

A new CBO report shows that the national debt outlook worsened from last year’s projections.