Smart Fiscal Policies For A Better Future

By Wendy Edelberg

This paper is part of a new initiative from the Peterson Foundation to help illuminate and understand key fiscal and economic questions facing America. See more papers in the America's Fiscal and Economic Outlook series.

This is the moment to strengthen the social insurance system and to enact an ambitious federal investment package, while raising tax revenue and cutting back on spending in ways that would largely offset those costs. Together, those policy changes would make the US economy more resilient and productive over the longer term. Additionally, they would broaden the degree to which prosperity in the United States is shared across workers and families. The current rapid economic recovery and expected slowing over the next year creates risks that policymakers should heed. Nonetheless, the policy proposals that Congress is currently considering would not notably add to those risks. Nor would the policies worsen the long-term challenge created by the projected fiscal trajectory under current law. That challenge would be best addressed by policies put in place over the next decade to raise substantial revenue and reform certain mandatory spending programs.

Changes to the Social Insurance System

Nearly everyone in the United States directly benefits from the social insurance system at some point in their lives. Moreover, everyone indirectly benefits from it — either from knowing the system would be there for them during some unexpected hardship or simply because it helps to support the overall economy.

How does the social insurance system reduce income inequality and poverty?

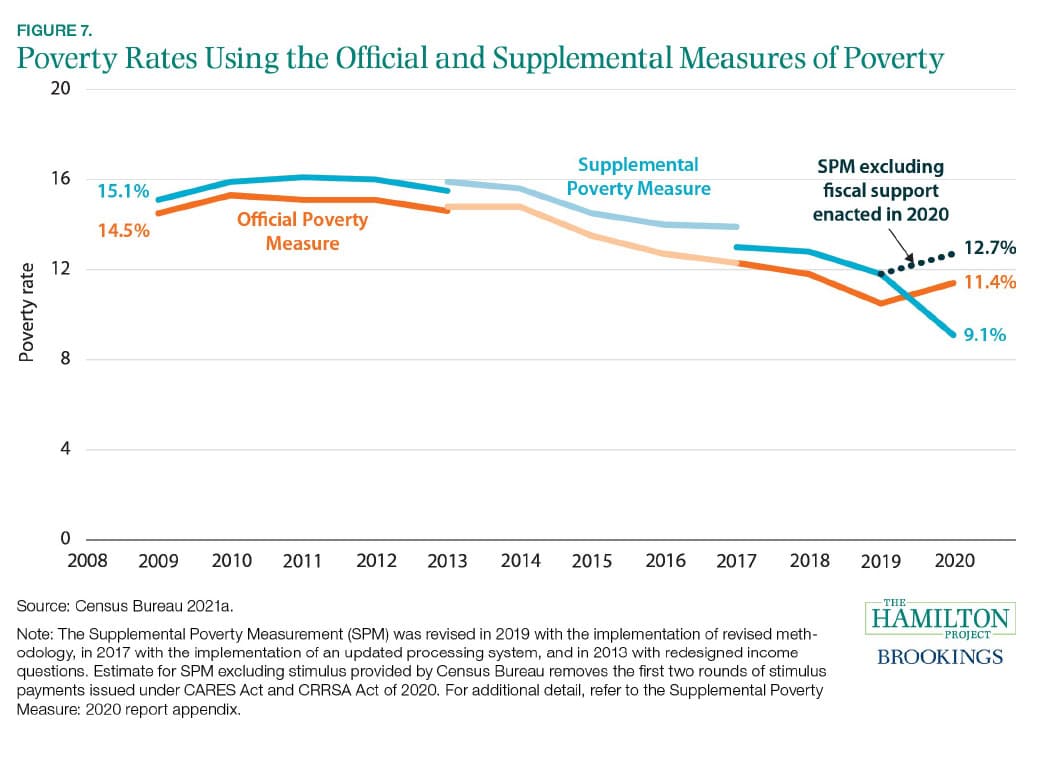

Using a measure of poverty that includes benefits from federal programs (the Supplemental Poverty Measure, or SPM), data show that in recent years social insurance programs had cut the SPM poverty rate in half after post-tax-and-transfer income is taken into account. As a result of the enormous fiscal support provided to households in 2020, the percentage of the US population in poverty, as measured by the SPM, fell from 12 percent to 9 percent; if Congress had not enacted relief for families, SPM poverty would have risen to 13 percent rather than falling to 9 percent.

With respect to children, in 2019 the child poverty rate before benefits and taxes was 20 percent. After benefits and taxes are taken into account, the child poverty rate was 13 percent. In 2020, owing to the robust fiscal support in the face of a massive economic shock, the SPM poverty rate for children fell to 10 percent. Nonetheless, for some groups of children, poverty rates after taxes and transfers remained very high. Data from 2015 highlights the disparities: the National Academy of Sciences found that in that year, child poverty rates for Black and Hispanic children were more than twice as high as non-Hispanic white children. The same report found that children of single parents endure double the poverty rate of a two-parent household (NAS, 2019).

In 2021, continued fiscal support — particularly the full refundability of and the increase in the child tax credit and increases to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) maximum benefit — as well as the continued labor market recovery should help to lift households out of poverty.

How would the proposed policies alleviate poverty, reduce inequality, improve well-being, and make the economy more resilient?

The successes in 2020 and 2021 of expanding and improving our social insurance system show some of the potential of making improvements in policy. Making some policies permanent would make sustained progress in reducing post-tax-and-transfer poverty and provide more insurance protection to families.

In this section, I summarize evidence for the benefits of reforming and expanding the social insurance system in the following illustrative areas: the Child Tax Credit, child care, paid leave, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and health care.

Child Tax Credit (CTC). Extending the changes that the American Rescue Plan (ARP) made to the CTC for 2021 — most importantly, making permanent the full refundability of the tax credit — would lock in place the enormous good this policy is doing for child poverty rates. Those changes the ARP made to the CTC, along with the other measures in the ARP, are projected to reduce poverty among children in 2021 from 14 percent to 8 percent (CPSP 2021). Indeed, more than 400 economists signed onto a letter supporting this change, based on evidence that CTC reduces child poverty and improves academic and long-term outcomes for children without affecting parental labor supply (Hoynes and Schanzenbach 2021).

Child care. The current policy proposal would make permanent the recent expansion of the Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CCDTC) and grants and tax subsidies aimed at raising wages of child-care providers. Those changes would help families with earnings too low to owe federal income tax afford child care and would improve the quality of child care and early childhood education, the benefits of which are well-documented. Together, the changes would boost the labor supply of parents of young children.

Paid leave. Standing up a federal paid family and medical leave program would improve children’s health, reduce worker turnover, and increase labor force participation with perhaps the largest effects for disadvantaged children and mothers.

Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). The current proposal would make permanent the recent expansion of the EITC for adults without children. Doing so would reduce poverty and income inequality and increase labor force participation.

Health insurance. If Congress made permanent the expansions to health-insurance premium tax credits and cost-sharing subsidies included in the ARP, the uninsured rate would fall by 13.6 percent (4.2 million) and lower-income households would be more financially secure (Banthin et al. 2021). Further expansions in access to Medicaid would do more to extend access to health care, where we have ample evidence that access increases annual health-care use among child and adults and improves the quality of life.

The effect on the economy of the reconciliation package and the bipartisan infrastructure package

The effective expansion of the social insurance system, some right-sizing in tax revenues, and investments in social and physical infrastructure would make the economy more productive and resilient over the longer term and lead to greater well-being and more equitably shared growth.

Moreover, the reconciliation package in combination with the bipartisan infrastructure package would not create notable inflation risk in the near term. The recent increase in inflation is largely attributable to the recent burst in consumer demand, which has outpaced supply, and also to various disruptions in global supply chains. Policymakers across many countries are rightfully paying attention. The timing of spending and revenue changes created by the policies under consideration would mean that consumer demand would be boosted only modestly, on net, over the next year or two.

Fiscal trajectory little changed but still a challenge

Policymakers have stated their goal is to include increases in tax revenues and decreases in spending that would fully offset the decreases in revenue and increases in spending. If something close to a full offset is achieved, the reconciliation package would do little to the projected debt trajectory.

Still, the US faces long-term fiscal challenges reflected in the trajectory of federal borrowing under current law — and, more importantly, the expectation of that trajectory by households and financial market participants. Empirical evidence suggests that with higher levels of deficits and debt, private domestic investment shrinks and the interest rate that the US pays on Treasury securities rises (Gamber and Seliski, 2019). However, those magnitude of those consequences is relatively modest in the context of the overall US economy. More of concern, observers worry that if those lending to the US government develop long-term worries about significant inflation risk or the value of the US dollar, that could lead to an abrupt increase in interest rates and trigger a fiscal crisis.

Nonetheless, in the decades before the pandemic, despite sometimes alarming long-term projections of federal borrowing, interest rates were on an overall downward trajectory. The recent episode has highlighted that interest rates on Treasury securities are determined by many factors in addition to the extent of US borrowing. Despite a run-up in the debt as a share of GDP from 79 percent in fiscal year 2019 to an estimated 103 percent in 2021, the yield on 10-year Treasury securities fell from 1.8 percent in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 1.3 percent in the third quarter of 2021. Over the next decade, debt as a share of GDP is projected to rise only modestly under current law. And, notably, that baseline includes roughly a doubling of the 10-year rate. So, an increase in interest rates is not, on the face of it, a risk to that debt trajectory; an increase in rates is already reflected in that trajectory. In sum, the fiscal trajectory is not an urgent challenge that policymakers need to take on in this legislative effort.

Beyond the next decade, debt as a share of GDP is indeed projected to rise — with rising interest costs and rising spending on major health care programs coupled with relatively flat revenues as a share of GDP. However, this reconciliation package — even if the estimates end up showing it would modestly increase the cumulative deficit over the next decade — would not meaningfully worsen those challenges. To take on the long-term fiscal challenges, over the next decade policymakers should enact significant increases in tax revenues and reform mandatory spending programs.

The long-term economic effects

An essential aspect of a federal budget is raising revenue, and it is virtually impossible to raise revenue without creating some negative incentives to work or to invest. The tax provisions that raise revenue that are were put forward by the House Ways and Means Committee would raise substantial revenue and have only modest negative effects on incentives.

Because the policies would undo some of the changes enacted as part of the 2017 tax act, it is instructive to consider how those prior changes were estimated to affect the economy. CBO, as well as a broad consensus of other groups, estimated that the 2017 tax act boosted the level of projected economic output in the longer term by less than 1 percent, with essentially no effect on the long-term growth rate. More specifically, CBO estimated that positive incentive effects on spending on nonresidential fixed investment raised the level of GDP after several years by less than one-half percent (CBO 2018).

Economists are currently debating whether effects on investment following the enactment of the 2017 tax act were smaller than projected (Gale and Haldeman 2021; Gravelle and Marples 2019; Kopp et al. 2019). One reason for that debate — and why it won’t ever be definitively settled — is that the projected effects were themselves small relative to the size of the US economy. As a result, it is difficult to disentangle what happened to investment from the tax act or from the many other effects and economic developments.

Similarly, consider how the 2017 tax act cut effective marginal tax rates on labor income — averaged among all workers in the US — by a little over 2 percentage points at its peak. That was estimated to increase average hours supplied by the workforce by about a quarter of a percent. The House Ways and Means Committee proposal includes a similarly sized increase in the effective marginal tax rates on labor income — but only for a small portion of the labor force comprised of the highest income people. If that increase in tax rates were enacted, the aggregate effect on labor supply would be small enough that we likely could not separately identify it.

Nonetheless, the increase in effective marginal tax rates for the highest income earners is not the only aspect of the reconciliation package that would dampen incentives to work. To some degree, people work as many hours as they do because they are financially desperate, or because they fear financial hardship owing to such events as losing a job or suffering from a health event. Although the vast majority of people who benefit from the social insurance system work for pay (for example, well over 90 percent of families receiving the Child Tax Credit [Goldin and Michelmore 2020]), a lessening of those factors could reduce hours worked per week. To put such effects in context, policymakers should focus on what a policy’s primary goal is: providing insurance, improving well-being, increasing labor force participation and hours worked per week, or raising revenue.

While the revenue raisers in the reconciliation package would have muted negative effects on incentives to work and invest, other policies would increase the incentives to work and invest. For example, improving access to high-quality and affordable child care and ensuring that workers have access to paid family leave would lower the cost of working among parents of young children and thus increase their supply of labor. It would also, over the longer term, improve the earning potential of those children who benefit. As another example, expanding the EITC would increase labor force participation. In addition, with a larger and more productive workforce, firms would have greater incentives to invest in the US and expand the capital stock.

Conclusion

Although I have focused on the fiscal effects and the aggregate economic effects of the policies under consideration, those should not be the only — and perhaps not even the primary — points of consideration. The tax provisions being proposed, and indeed many of the policies being proposed, would improve well-being and ensure that our prosperity is more widely shared. GDP estimates and net deficit effects attract attention because they are numbers with seemingly a lot of precision. And numbers have power. However, I urge policymakers to step back from those estimates and consider whether the policies they are debating would move us closer to the kind of society we want to live in.

References

Appelbaum, Eileen and Ruth Milkman. 2011. “Employer and Worker Experiences with Paid Family Leave in California.” Center for Economic and Policy Research, Washington, DC.

Bailey, Martha, Tanya Byker, Elena Patel, and Shanthi Ramnath. 2019. “The Long-Term Effects of California’s 2004 Paid Family Leave Act on Women’s Careers: Evidence from U.S. Tax Data.” Working Paper 26416, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Bastian, Jacob, and Katherine Michelmore. 2018. “The Long-Term Impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit on Children’s Education and Employment Outcomes.” Journal of Labor Economics 36 (4): 1127–63.

Bastian, Jacob. 2020. “The Rise of Working Mothers and the 1975 Earned Income Tax Credit.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 12 (3): 44–75.

Banthin, Jessica, Matthew Buettgens, Michael Simpson, Robin Wang. 2021. “What if the American Rescue Plan’s Enhanced Marketplace Subsidies Were Made Permanent? Estimates for 2022.” Urban Institute, Washington, DC.

Baughman, Reagan., and Stacy Dickert-Conlin. 2009. “The Earned Income Tax Credit and Fertility.” Journal of Population Economics. 22: 537-63

Baum, Charles L., and Christopher Ruhm. 2013. “The Effects of Paid Family Leave in California on Labor Market Outcomes.” Working Paper, Washington DC, NBER

Boushey, Heather, Ann O’Leary, and Alexandra Mitukiewicz. 2013. “The Economic Benefits of Family and Medical Leave Insurance.” Center for American Progress, Washington, DC.

Braga, Breno, Fredric Blavin, Anuj Gangopadhyaya. 2020. “The Long-Term Effects of Childhood Exposure to the Earned Income Tax Credit on Health Outcomes.” Journal of Public Economics 190.

Byker, Tanya S. 2016. “Paid Parental Leave Laws in the United States: Does Short-Duration Leave Affect Women’s Labor-Force Attachment?” American Economic Review 106 (5): 242–46.

Cascio, Elizabeth. 2021. “Early Childhood Education in the United States: What, When, Where, Who, How and Why.” Working Paper. NBER. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Caven, Meg, Noman Khanani, Xinxin Zhang, and Caroline E. Parker. 2021. “Center- and Program-Level Factors As- sociated with Turnover in the Early Childhood Education Workforce.” National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, US Department of Education, Washington, DC.

Center on Poverty and Social Policy (CPSP). 2021. “A Poverty Reduction Analysis of the American Family Act.” Center on Poverty & Social Policy, Columbia University, New York.

Chetty, Raj, John N. Friedman, and Jonah E. Rockoff. 2011, November. “New Evidence on the Long-Term Impacts of Tax Credits.” Internal Revenue Service, U.S. Department of the Treasury, Washington, DC.

Congressional Budget Office (CBO) 2018. “Appendix B: The Effects of the 2017 Tax Act on CBO’s Economic and Budget Projections. The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018-2028. 105-130 Congressional Budget Office, Washington, DC,

— 2020. “Who Went Without Health Insurance in 2019, and Why?” Congressional Budget Office, Washington, DC.

Data USA. 2020. Childcare workers: Race and Ethnicity.

Davis, Elizabeth E. and Aaron Sojourner. 2021. “Increasing Federal Investment in Children’s Early Care and Education to Raise Quality, Access, and Affordability.” The Hamilton Project, Washington, DC.

Eissa, Nada, and Jeffrey B. Liebman. 1996. “Labor Supply Response to the Earned Income Tax Credit.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 111 (2): 605–37.

Gamber, Edward and John Seliski. 2019. “The Effect of Government Debt on Interest Rates.” Working Paper 2019-01. Congressional Budget Office, Washington, DC.

Gale, William G, and Claire Haldeman, 2021. “Searching for the Supply Side Effects of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

Goldin, Jacob, and Kathrine Michelmore. 2020. “Who Benefits from the Child Tax Credit?” Working Paper, National Bureau of Economic Research. Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Gravelle, Jane G., and Donald J. Marples, 2019. “The Economic Effects of the 2017 Tax Revision: Preliminary Observations.” Congressional Research Service, Washington, DC.

Hoynes, Hilary, Doug Miller, and David Simon. 2015. “Income, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and Infant Health.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7 (1): 172–211.

Hoynes, Hilary, Jesse Rothstein. 2016. “Tax Policy toward Low-Income Families.” Working Paper 22080, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Hoynes, Hilary, and Ankur J. Patel. 2018. “Effective Policy for Reducing Poverty and Inequality?: The Earned Income Tax Credit and the Distribution of Income.” Journal of Human Resources 53 (4): 859–90.

Kopp, Emanuel, Daniel Leigh, Susanna Mursula, and Suchanan Tambunlertchai, 2019. “U.S. Investment Since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.” Working Paper, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC.

Malik, Rasheed. 2019. “Working Families Are Spending Big Money on Child Care.” Center for American Progress. Washington, DC.

McCoy, Dana Charles, Hirokazu Yoshikawa, Kathleen M. Ziol-Guest, Greg J. Duncan, Holly S. Schindler, Katherine Magnuson, Rui Yang, Andrew Koepp, and Jack P. Shonkoff. 2017. “Impacts of Early Childhood Education on Medium-and Long-Term Educational Outcomes.” Educational Researcher. 46 (8): 474-87.

Meyer, Bruce D., and Dan T. Rosenbaum. 2001. “Welfare, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and the Labor Supply of Single Mothers.” Quarterly Journal of Economics (August): 1063–14.

National Academy of Sciences (NAS). 2019. A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

Neumark, David, Brian Asquith, and Brittany Bass. 2019. “Longer-Run Effects of Anti-Poverty Policies on Disadvantaged Neighborhoods.” Contemporary Economic Policy 38 (3): 409–34.

Porter, Noriko. 2012. “High Turnover among Early Childhood Educators in the United States.” Child Research Net, Oakland, CA.

Rossin, Maya. 2011. “The Effects of Maternity Leave on Children’s Birth and Infant Health Outcomes in the United States.” Journal of Health Economics 30 (2): 221–39.

— 2013. “WIC in Your Neighborhood: New Evidence on the Impacts of Geographic Access to Clinics.” Journal of Public Economics 102 (2013): 51–69.

Rossin-Slater, Maya, Christopher Ruhm, and Jane Waldfogel. 2011. “The Effects of California’s Paid Family Leave Program on Mothers’ Leave-Taking and Subsequent Labor Market Outcomes.” Working Paper 17715, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Ruhm, Christopher. 2000. “Parental Leave and Child Health.” Journal of Health Economics 19: 931–60.

Saez, Emmanuel. 2010. “Do Taxpayers Bunch at Kink Points?” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 2 (3): 180–212.

Schanzenbach, Diane Whitmore, and Michael R. Strain. 2020. “Employment Effects of the Earned Income Tax Credit: Taking the Long View.” Discussion Paper 13818, IZA, Bonn, Germany.

Vogtman, Julie. 2017. “Undervalued: A Brief History of Women’s Care Work and Child Care Policy in the United States.” National Women’s Law Center, Washington, DC.

Whitebook, Marcy, Deborah Phillips, and Carollee Howes. 2014. “Worthy Work, STILL Unlivable Wages: The Early Childhood Workforce 25 Years after the National Child Care Staffing Study.” Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley, CA.

Workman, Simon, and Steven Jessen-Howard. 2018. “Where Does Your Child Care Dollar Go: Understanding the True Cost of Child Care for Infants and Toddlers.” Center for American Progress, Washington, DC.

About the Author

Wendy Edelberg is the director of The Hamilton Project and a senior fellow in Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution. Edelberg joined Brookings in 2020, after more than fifteen years in the public sector. She is also a Principal at WestExec Advisors. Most recently, she was Chief Economist at the Congressional Budget Office. Prior to working at CBO, Edelberg was the executive director of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, which released its report on the causes of the financial crisis in January 2011. Previously, she worked on issues related to macroeconomics, housing, and consumer spending at the President’s Council of Economic Advisers during two administrations. Before that, she worked on those same issues at the Federal Reserve Board.

Edelberg is a macroeconomist whose research has spanned a wide range of topics, from household spending and saving decisions, to the economic effects of fiscal policy, to systemic risks in the financial system. In addition, at CBO and the Federal Reserve Board, she worked on forecasting the macroeconomy. Edelberg received a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Chicago, an M.B.A. from the University of Chicago, and a B.A. from Columbia University.

Expert Views

America's Fiscal and Economic Outlook

We asked twelve leading experts to share their views on the most important fiscal and economic questions facing America.

Their insights help illuminate and improve the understanding of this critical moment, with our economy in recovery, our debt rising unsustainably, and our nation still grappling with a devastating pandemic.

Download the ebook version of all the papers in the series.