Economic Impact Payments, also referred to as stimulus checks, were a key component of the fiscal response to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Those payments, which totaled up to $1,200 for individuals ($2,400 for married couples) plus $500 per qualified child, mitigated the loss of employment-based income for many households and temporarily eased the economic damage from the pandemic. However, some analysts contend that the program should have been implemented with a lower income threshold. Overall, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) anticipates that the program will cost a total of $292 billion through 2021.

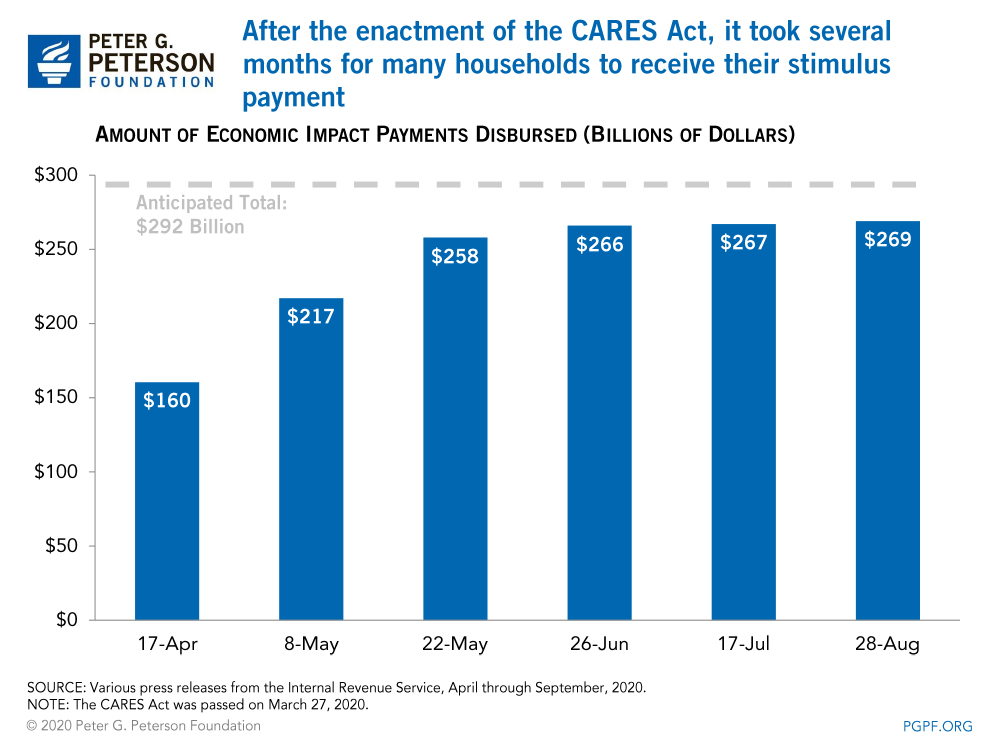

How Fast Were the Stimulus Checks Sent Out?

More than half of the payments were sent out in the first three weeks, much faster than similar payments had been issued in previous recessions; however, some households didn’t receive their funds until several months later.

As of April 17, three weeks after the impact payments were enacted through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, about $160 billion of the funds — accounting for 55 percent of the anticipated total — had been sent to Americans’ bank accounts electronically via direct deposit. That disbursement was significantly faster than similar payments that had been issued during the economic downturn of 2001 and in 2008 during the Great Recession; it took about six weeks for the initial payments to go out in 2001 and about three months for the 2008 funds.

However, many lower-income Americans were excluded from that initial disbursement due to a lack of direct deposit capability or the lack of a bank account altogether. As such, those individuals had to wait for physical checks or debit cards, the first of which were not sent out until May. As of May 8, six weeks after the payments had been approved by Congress and the President, 26 percent of the funding had yet to be disbursed. That number dropped to 12 percent by May 22 and was most recently at 8 percent as of August 28, the latest date for which data are available. Given the historic levels of unemployment and economic damage caused by the pandemic, especially to lower-income Americans, the timeliness of that support could have been crucial.

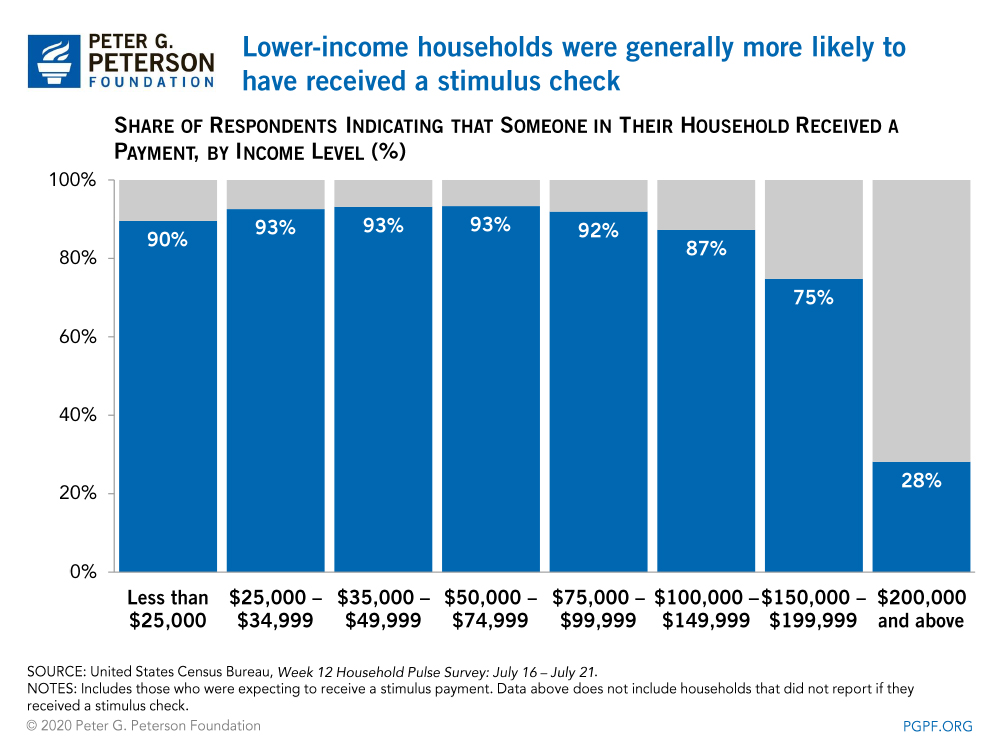

Did the Stimulus Payments Go to Households Most Financially Hurt by the Pandemic?

One of the primary goals of the payments was to alleviate the economic hardship Americans faced due to the pandemic — especially for lower-income Americans, who were more likely to have been financially affected. Data from a household survey published by the U.S. Census Bureau (which presented results as of July 21) and other studies show the payments were effective in accomplishing that goal.

About 85 percent of U.S. households have already received, or anticipate receiving, a payment. Generally, that number was higher for lower- and middle-income households and gradually declined for those earning more than $75,000 a year — the income threshold at which the payments were reduced for single individuals. On the other hand, more affluent households were much less likely to receive the funds; only 28 percent of households earning more than $200,000 a year received an Economic Impact Payment.

Overall, the payments were effective in helping those who were financially affected by the pandemic as the majority of households who had lost employment-based income received a payment. In fact, according to a study by the American Enterprise Institute, the impact payments played a pivotal role in preventing many Americans from falling into poverty during the pandemic.

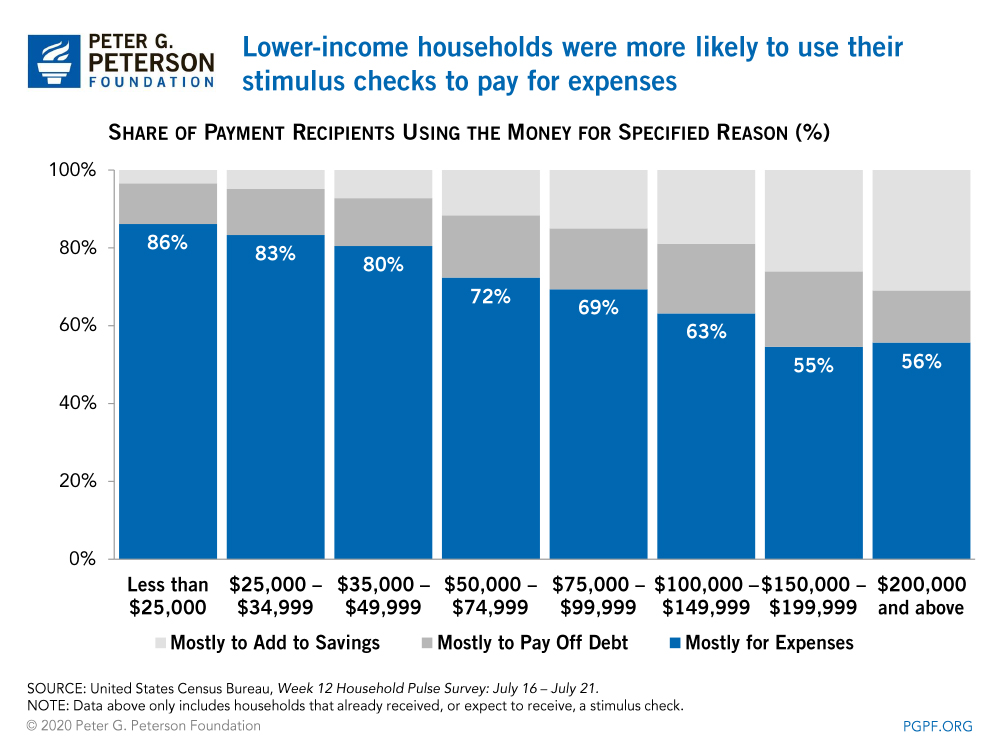

How Did Americans Spend Their Stimulus Payment?

Because the payments helped mitigate the loss of employment-based income for many lower- and middle-income households, those families were more likely to use the funds to pay for their expenses as opposed to saving it or using it to pay off existing debt. On average, 80 percent of households earning less than $75,000 a year used their impact payment primarily to pay for expenses; that figure was only 55 percent for households earning $150,000 or more. Higher-income households, on the other hand, were more likely to add the money to their savings or use it to reduce any outstanding household debt — activities that do little to stimulate the economy. As such, some analysts have questioned whether the payments should have started phasing out at a lower threshold.

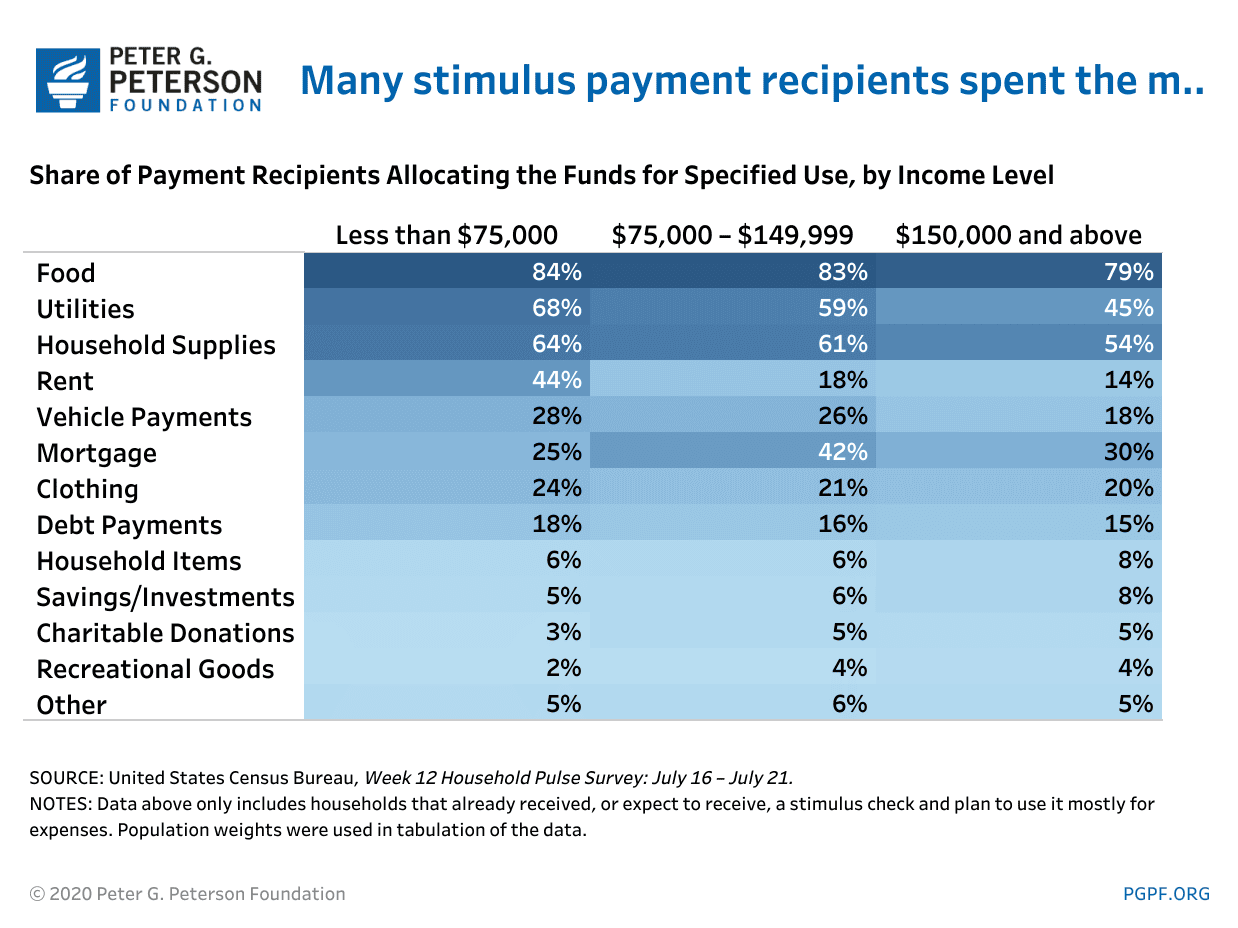

In particular, the households that used their payment mostly for expenses spent that money on living expenses such as food and household supplies as well as on payments like utilities, rent, and mortgages. Those spending patterns demonstrate that many Americans used the money to meet their ongoing financial needs.

How Did the Stimulus Payments Affect the Economy?

Largely due to the spending patterns of less-affluent Americans, the Economic Impact Payments provided a modest boost to the economy. However, that boost was concentrated in certain industries.

Because households were more likely to spend the money on items such as food and household supplies as well as on payments like utilities, rent, mortgages, and credit cards, those sectors saw the largest increases in consumer spending from the impact payments. Compared to similar direct payments in the past, according to an analysis by the National Bureau of Economic Research, the impact payments weren’t used as often to buy goods such as electronics, furniture, or cars. Therefore, the 2020 payments didn’t have as much of an effect on those areas of the economy.

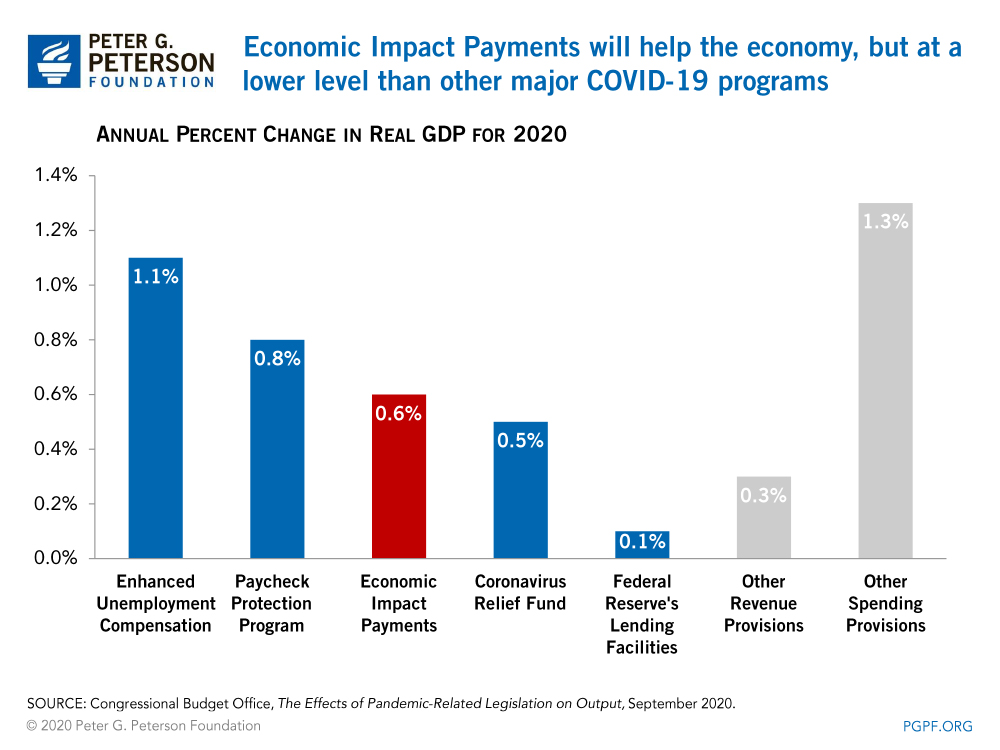

Overall, the impact payments are expected to increase the country’s real (inflation-adjusted) economic output by 0.6 percent in 2020 according to CBO; by comparison, that amount is about one-half of the economic boost provided by the enhanced unemployment benefits and 33 percent less than the boost from the Paycheck Protection Program and related small business provisions. The payments are expected to boost the economy by 60 cents for every dollar of budgetary cost.

The Economic Impact Payments helped alleviate the financial hardship faced by many Americans due to the COVID-19 pandemic and provided a modest boost to the economy. However, many of the payments went to higher-income households not financially affected by the pandemic who simply saved the money or used it to pay off existing debt. By understanding the benefits and shortcomings of the program, policymakers can improve the effectiveness of any future iteration of the program.

Image credit: Photo by Eduardo Munoz Alvarez/Stringer/Getty Images

Further Reading

The Fed Held Its Target Range After Reducing the Short-Term Rate Three Meetings in a Row

High interest rates on U.S. Treasury securities increase the federal government’s borrowing costs.

What’s the Difference Between the Trade Deficit and Budget Deficit?

The terms “budget deficit” and “trade deficit” can be conflated, but they are distinct measurements of important fiscal and economic concepts.

What Types of Securities Does the Treasury Issue?

Learn about the different types of Treasury securities issued to the public as well as trends in interest rates and maturity terms.