Healthcare spending in the United States accounts for a sizable share of the economy and continues to grow rapidly. A particularly fast-growing portion of healthcare spending goes to prescription drugs, much of it covered by the federal government. In fact, about one-third of retail prescription drug spending is attributable to Medicare. The Inflation Reduction Act, signed into law in 2022, contains a number of provisions aimed at combatting the rising costs of prescription drugs for the federal government, including allowing Medicare to negotiate some pricing.

Spending on Prescription Drugs Is Higher in the u.s. Compared to Other Countries

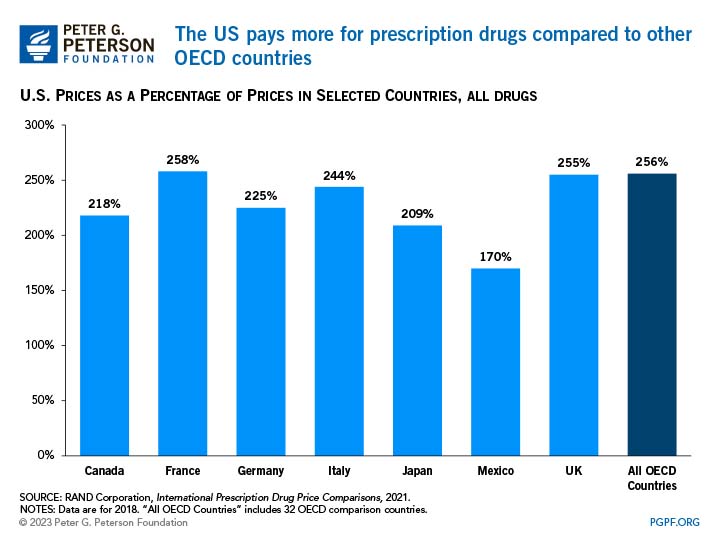

The United States spends nearly three times the average of other developed countries per capita on healthcare, which is partly due to high drug costs. The United States has the highest total spending on prescription drugs out of all the countries that belong to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), an organization comprised of 38 countries that works together to find solutions to common challenges and promote better economic policies. A 2021 study by the RAND Corporation, a nonprofit research organization, found that the cost of brand-name drugs in the United States was more than triple the cost of those same drugs in other developed countries. For example, on average the United States pays 2.5 times more than France does for all drugs. One reason is the ability of pharmaceutical companies to extend or create new patents in the United States — many of which are not actually for new drugs. Abuse of the patent process can decrease competition, restrict generic versions from being produced, and thereby allow companies to charge higher prices here compared to other countries.

Several other factors also contribute to other countries paying different prices on prescription drugs, such as the number of and types of payers, the availability and prices of generic or biosimilar alternatives, the role of pharmaceutical benefit managers, and the regulation or benchmarking of prices.

Spending on Prescription Drugs by Medicare Is Particularly High

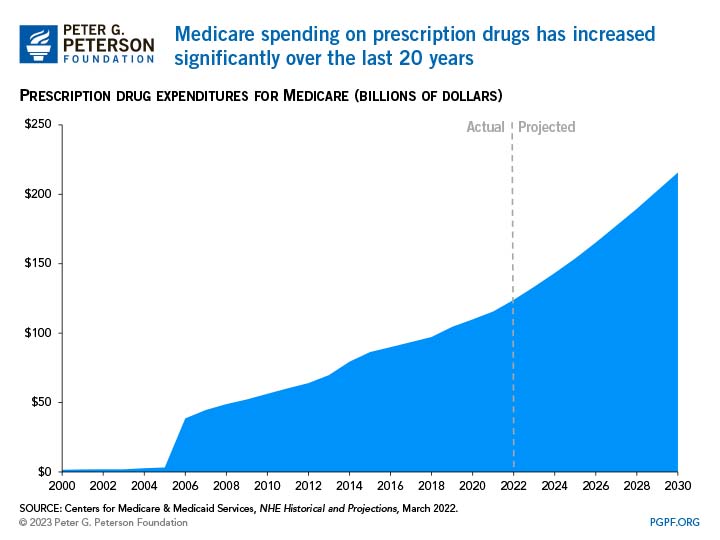

Relative to other payers in the U.S. healthcare system, Medicare’s costs for prescription drugs are high and have been rising quickly. The benefit for prescription drugs in Medicare went into effect in 2006 when Medicare began to provide coverage for enrollees under its “Part D” program. Spending on prescription drugs under Medicare increased from $39 billion in 2006 to $116 billion in 2021.

One reason that spending on retail prescription drugs has increased is that as medicine and science have evolved, more specialty drugs have become available to treat certain conditions. For example, there were no treatment options for conditions such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) before 1987 but now there are more than 30 FDA-approved HIV medications. Specialty drugs can also be particularly expensive, which pushes up the aggregate cost of prescription drugs in the United States. Generic drugs, which are cheaper than brand-name drugs, have also become more widespread, but the cost of specialty drugs is so high that they still drive Medicare’s growing costs. Researchers found that the top 50 best-selling drugs covered by Medicare Part D accounted for 37 percent of net Part D spending in 2019.

The sheer volume of drugs available has also driven the rise in costs. Per enrollee use of prescription drugs for Medicare Part D beneficiaries has increased from an average of 48 prescriptions per year in 2009 to 54 per year in 2018. In many cases, the use of drugs has become a substitute for other routes of care. For example, researchers found that stents and surgery were no better than medication and lifestyle changes at reducing cardiac events.

How Would Medicare Negotiate Prices?

Prior to enactment of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), Medicare was prohibited from negotiating prescription drug prices directly with manufacturers, which contributed to the government having to pay for medications at relatively higher pricesi. The IRA authorizes the federal government to directly negotiate prices for a limited number of drugs covered by Medicare. Under the enacted provisions, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) will be allowed to negotiate prices for up to 10 drugs in 2025, an additional 15 in 2027, 15 more in 2028, and finally another 20 drugs in 2029 and after.

High costs are concentrated among a relatively small number of drugs; the most costly 100 drugs account for nearly 50 percent of all Part D spending. The goal of price negotiation is to reach a “maximum fair price” that more closely matches the Average International Market price, which represents the average price in six countries: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom. The agreed-upon price would then be made available to insurers and organizations that sponsor Medicare Part D plans as well as commercial payers in group and individual markets. If drug companies do not comply with the negotiation process, a maximum excise tax of 95 percent would be applied.

Will Negotiating Drug Prices Save Money?

Overall, allowing HHS to negotiate drug prices in Medicare is expected to reduce costs for the federal government and for consumers. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that all of the provisions related to prescription drugs in the IRA will save the federal government $286 billion over the upcoming decade. Of that, the price negotiating provision is projected to reduce spending by nearly $102 billion over 10 years.

The concept is already in practice in other agencies of the federal government that provide health services. The Veterans Health Administration, Department of Defense, and Medicaid all have the power to negotiate drug prices, and they pay less than Medicare, on average, for top-selling brand-name drugs. In a recent report, the Center for American Progress wrote that “lowering drug prices through negotiation, inflationary rebates, and insulin and cost-sharing caps would allow people — especially those with chronic conditions and disabilities — to access the treatment they need.”

Proponents of the mechanism for price negotiation believe that allowing Medicare to directly negotiate with pharmaceutical companies will provide the leverage needed to lower drug costs. In particular, Medicare may be more able to negotiate lower prices than private plans for the most costly drugs for which there are no substitutes. Opponents counter that there is no need for the government to be a negotiating player since the private sector already negotiates prices for Medicare Part D. Furthermore, the pharmaceutical industry has raised concerns about allowing Medicare to negotiate prices, arguing that doing so will reduce innovation, decrease companies’ return on investment, and subsequently lead to fewer drugs available in the future. CBO estimates that the proposal would lead to 10 fewer drugs out of 1,300 brought to market over the next 30 years.

Conclusion

The price of prescription drugs in the United States is high and rising, with costly consequences both for consumers and for the federal balance sheet. Allowing Medicare to negotiate drug prices is one promising policy that lawmakers could consider to reduce healthcare spending, lower costs for consumers, and put our nation on a stronger and more sustainable fiscal path.

i Prices for retail prescription drugs covered by Medicare Part D were are generally determined through private plan sponsors that negotiate with pharmaceutical companies. For Medicare Part B, which covers drugs administered by physicians, Medicare reimburses providers 106 percent of the Average Sales Price, which is the average price to all non-federal purchasers (including rebates) in the United States.

Image credit: Photo by Willie B. Thomas/Getty Images

Further Reading

Quiz: How Much Do You Know About Healthcare in the United States?

The United States has one of the largest and most complex healthcare systems in the world. Take our healthcare quiz to see how much you know about the cost and quality of the U.S. healthcare system.

How Did the One Big Beautiful Bill Act Change Healthcare Policy?

The OBBBA adds significantly to the nation’s debt, but its healthcare provisions lessen that impact by $1.0 trillion.

Infographic: U.S. Healthcare Spending

Improving our healthcare system to deliver better quality care at lower cost is critically important to our nation’s long-term economic and fiscal well-being.