Sequestration is a budget procedure used by lawmakers to cancel or limit funding in order to meet budget goals. It can be intended as an enforcement mechanism to discourage lawmakers from violating a specific budgetary goal or to encourage lawmakers to enact legislation that achieves a desired budgetary outcome. A potential sequestration was most recently included in the Fiscal Responsibility Act (FRA) and could be triggered depending on when Congress completes the appropriation process for fiscal year 2024.

Legislative Provisions for Sequestration Currently in Effect

Sequestration is currently being used as an enforcement tool for budgetary goals set forth in three pieces of legislation.

1. Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023

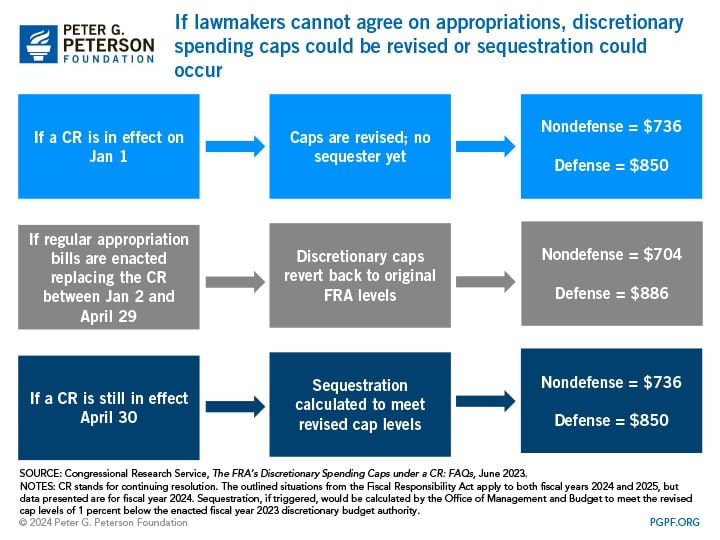

As part of the deal to suspend the debt limit in June 2023, policymakers implemented budget caps on defense and nondefense discretionary spending for fiscal years 2024 and 2025. An alternate (revised) set of caps were included in the FRA to encourage lawmakers to enact full-year appropriations in a timely fashion.

Specifically, unless all full-year appropriation bills have been enacted by April 30, 2024 (meaning there is no continuing resolution (CR) still in effect by that date), then the revised cap levels would govern the calculation of potential across-the-board cuts. If Congress and the President enact the regular 12 appropriation bills by April 29, 2024, the caps would revert to the original levels in the FRA. The same procedures would be in place for 2025. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates that relative to the Consolidated Appropriations Act enacted earlier in March and the CR in place through March 22, defense spending would be subject to a sequestration to meet the revised caps for fiscal year 2024 of 1 percent (or $11 billion). Nondefense spending is currently below the revised caps and would not be subject to sequestration.

2. Legislation Extending the Budget Control Act of 2011

The sequestration provisions related to discretionary spending from the Budget Control Act expired in fiscal year 2021, but multiple pieces of legislation extended sequestration for some non-exempt mandatory spending. Most recently, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act allows the sequestration of certain mandatory spending through fiscal year 2031. Additionally, Medicare benefit payments are subject to sequestration of a maximum of 2 percent through fiscal year 2032 due to the enactment of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023.

3. Statutory Pay-As-You-Go Act of 2010 (PAYGO)

Statutory PAYGO, which is separate from the PAYGO rule in the Senate and the CUTGO rule in the House, requires that any new legislation that increases mandatory spending or decreases revenues must be fully offset by other spending or revenue changes so it is deficit neutral. If either the 5- or 10-year average cost of new legislation is greater than zero when Congress adjourns, sequestration would be triggered. Because the PAYGO sequester is limited to mandatory spending programs, most programs are completely or partially exempt from such cuts; Medicare benefit payments, for example, are limited to a maximum 4 percent cut. PAYGO sequestration can also be nullified if Congress waives the rule or resets the PAYGO scorecards, which track the costs or savings of each legislation, to zero.

How Is Sequestration Carried Out?

The concept of sequestration was established in 1985 in the Balanced Budget and Emergency Deficit Control Act (BBEDCA), which outlines the general rules on sequestration enforcement procedures. If a sequestration is triggered, the President is required to issue a sequestration order that must follow the requirements set forth in the BBEDCA. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is then responsible for determining the sequester amount, which budget accounts will be subject to the sequestration order, and the uniform percentage by which non-exempt budgetary resources must be reduced to achieve the total necessary reduction. Not all government programs are impacted by a sequestration order. Some programs, mostly mandatory ones such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, are either completely or partially exempt from sequestration. Most discretionary programs are considered non-exempt and are, therefore, subject to sequestration.

Sequestration in the Past

Although the threat of sequestration has spurred legislative action in the past, only two instances exist where a sequestration has been implemented. A sequester was written in BBEDCA as a backstop in case lawmakers could not reach an agreement on how to meet the Maximum Deficit Amount for each fiscal year in the act, meaning across-the-board cuts to non-exempt budgetary resources would transpire if not met. That occurred in 1986 and the sequestration resulted in a $24.3 billion cut from budget authority. Subsequent legislation was written to adjust the parameters of sequestration and deficit targets, but some of the design elements of BBEDCA serve as the basis for current sequestration language.

The Budget Control Act (BCA) of 2011 implemented budget caps on discretionary spending over fiscal years 2012 to 2021 and formed the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction, often referred to as the Super Committee, to produce legislation that reduced federal deficits by $1.5 trillion over that period. When the committee failed to produce such legislation, sequestration was triggered — automatically reducing spending for 2013 and lowering spending caps through 2021. A relatively small amount of mandatory spending was also subject to sequestration through 2021 (those provisions have subsequently been extended).

Impacts of Sequestration

Because sequestration is a blunt instrument, it can have some adverse consequences on federal programs and parts of the economy. One of the authors of the BBEDCA (also known as the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act) remarked, “It was never the object of Gramm-Rudman to trigger the sequester, the objective of Gramm-Rudman was to have the threat of the sequester force compromise and action.” The fact that cuts are indiscriminant means that sequestration does not allow for consideration of the priorities and needs of the government at a particular time. Sequestration is also temporary in nature, so it may not be effective in reducing long-term debt. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget projected that the 2013 sequester from the BCA would have no further effect on long-term debt beyond a small impact on interest costs. Sequestration can also lead to job losses (1.8 million projected job losses from the 2013 sequester — 1.5 million of which were in the private sector), disproportionate cuts across states, and slower economic growth.

Though sequestration can lead to less than ideal outcomes, it is an important tool lawmakers can use in the budget process to encourage action. For example, an analysis done by Brian Riedl, a senior fellow at Manhattan Institute, found that penalty defaults such as sequestration can be a key ingredient for a successful budget deal. Because it “raise[s] the cost of inaction to an unacceptable level, ” sequestration can strike the necessary balance in that it is unpleasant enough to encourage action, but not so unpleasant that one side is still willing to risk a sequester coming into play if a deal is not made.

Conclusion

Sequestration is a blunt tool used to hold lawmakers accountable to reach their budgetary goals and reduce deficits. However, when used as a long-term budgeting mechanism instead of the failsafe that it is designed to be, there are significant limitations to sequestration’s effectiveness with unpredictable or undesired impacts on government spending and the economy at-large. For lasting fiscal sustainability, lawmakers will need to target drivers of the debt to address the long-term, structural imbalance between spending and revenues.

Photo by Samuel Corum/Getty Images

Further Reading

Lawmakers are Running Out of Time to Fix Social Security

Without reform, Social Security could be depleted as early as 2032, with automatic cuts for beneficiaries.

Budget Basics: How Does Social Security Work?

Social Security is the largest single program in the federal budget and typically makes up one-fifth of total federal spending.

How Did the One Big Beautiful Bill Act Affect Federal Spending?

Overall, the OBBBA adds significantly to the nation’s debt, but the act contains net spending cuts that lessen that impact.