Government safety net and income security programs are a cornerstone of our economy, society and federal budget. Social Security and Medicare are America’s largest social programs, providing critical retirement and health benefits to millions. As a result of an aging population and rising healthcare costs, both Social Security and Medicare are on an unsustainable path.

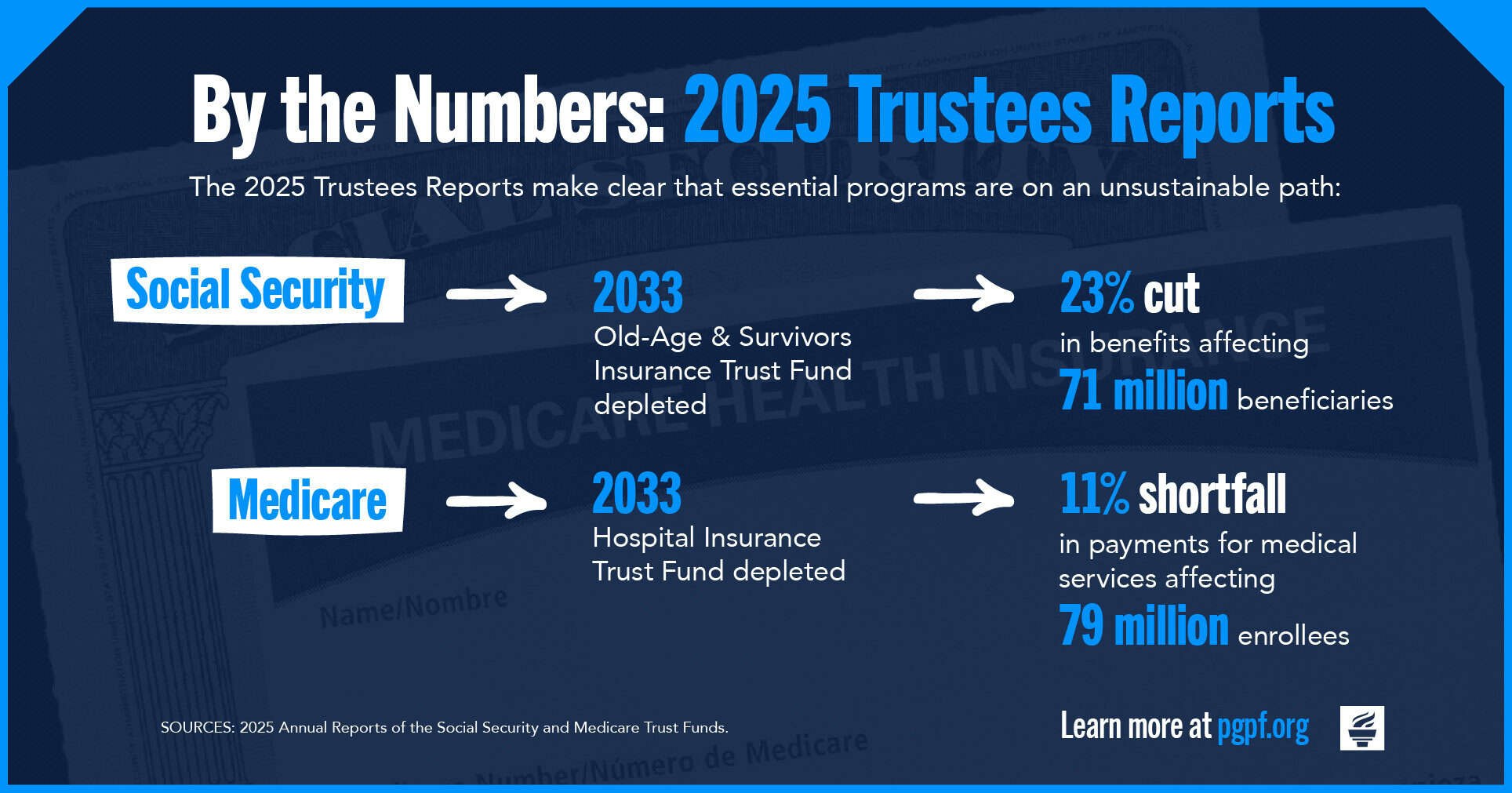

Every year, the Social Security and Medicare trustees provide a report on those programs’ finances and outlooks. The latest reports project that Social Security’s Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund will become depleted in 2033 and Medicare’s Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund will also become depleted in 2033. At that point, benefits for the respective programs would face significant and sudden automatic cuts, unless lawmakers make reforms before then.

- If lawmakers allow Social Security’s OASI Trust Fund to become depleted in 2033, 71 million beneficiaries would face across-the-board benefit cuts of 23 percent. According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB), benefits would be cut by $18,100 per year for the typical couple, if the recently passed One Big Beautiful Bill Act is also taken into account.

- If lawmakers allow Medicare’s HI Trust Fund to become depleted in 2033, there would be an 11 percent cut in payments to hospitals and other providers.

The good news is that it is entirely within policymakers’ control to shore up Social Security and Medicare and preserve them for the future. Doing so will not only protect millions of beneficiaries — especially our most vulnerable citizens — but will also provide stability and strength to our fiscal and economic outlook.

Other Social Programs:

In addition to Medicare and Social Security, there are a range of social programs serving Americans, including spending programs and tax benefits:

- Health programs — including Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and premium tax credits for low- and moderate-income people.

- Income Security Programs — including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Supplemental Security Income, Unemployment Compensation, the refundable portion of the Earned Income and Child Tax Credits.

Lawmakers do not provide specific funding levels for those social programs. Instead, they specify the rules of eligibility for benefits as well as the type and level of benefits that each person can receive. For example, the unemployment insurance program has eligibility criteria that, once met, allow an individual to receive a certain level of benefits. Total spending on the program depends on the number of people who file for unemployment, rather than a fixed amount of funding set by lawmakers.

Many policy solutions exist for improving the financial outlook of Social Security’s retirement program.

Increasing Social Security’s Payroll Tax Rate

One option to help shore up Social Security’s long-term solvency would be to increase the payroll tax rate, which is currently 12.4 percent (half paid by employees and half by employers) on wage earnings subject to the tax. According to an analysis from the Social Security Administration (SSA), increasing the payroll tax by 1 percentage point (from 12.4 percent to 13.4 percent) could raise $601 billion in new revenues for Social Security over a 10-year period and shrink the program’s 75-year shortfall gap, or long-range actuarial deficit, by 26 percent.

Increasing or Eliminating the Social Security Tax Cap

Another policy option to increase revenues for Social Security is to raise or eliminate the cap on the amount of income subject to the Social Security tax. In 2025, workers pay Social Security tax on only the first $178,100 of income. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), increasing the taxable income limit to 90 percent of earnings, or $305,100, would increase revenues by $728 billion and close the 75-year solvency gap by 21 percent. According to the SSA, eliminating the taxable maximum subject to the Social Security tax altogether would raise $3.2 trillion over 10 years. Such a reform would reduce the long-range actuarial deficit by 53 percent.

Adjusting Benefits

Another solution for improving the solvency of Social Security is to change the amount that retirees can receive when they first apply for benefits. Many proposals combine a reduction in benefits for high earners with an increase in benefits for lower earners. One such proposal is to establish a uniform social security benefit. If all beneficiaries received 150 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL), CBO estimates that spending would decrease by $283 billion. If benefits were pegged to 125 percent of the FPL, spending would decrease by $607 billion and reduce the long-range actuarial deficit by 183 percent.

Other options for adjusting benefits include slowing the growth of retirees’ benefits over time by changing the cost-of-living index. Many economists believe that Social Security uses an index that overstates inflation, so benefits grow faster than the true cost of living. They propose replacing the current index with chained-CPI, which is a more accurate measure of inflation. CBO estimates that such a reform would reduce spending by $204 billion over 10 years. SSA estimates that it would reduce the long-range actuarial deficit by 16 percent.

Importantly, most proposals that reduce benefits exempt those individuals who are in retirement, or near retirement (i.e., 55 years old and above). Many policymakers feel that this is a fairer way to reform the program, giving people sufficient time to prepare for their retirement.

Gradually Raising the Retirement Age

Given that overall life expectancy continues to increase, many policymakers have called for a modification to the program in which the full retirement age is gradually raised. According to an analysis from CBO, gradually increasing the full retirement age by two months per year until it reaches 70 would save $95 billion over a 10-year period. CBO estimates that the reform would close the structural mismatch between Social Security’s revenues and spending by 33 percent in the 75-year projection period. There are also important options to consider that would exempt those whose work includes demanding physical labor, as well as considerations for differences in life expectancy among different groups of Americans.

Including State and Local Government Employees in Social Security

Under current law, state and local governments can opt out of enrolling their employees in Social Security if they instead provide a separate retirement plan, such as a pension. Today, roughly one-quarter of all state and local government employees are not covered by Social Security, and thus are not subject to the Social Security payroll tax. According to a 2020 CBO analysis, expanding Social Security coverage to include all state and local government employees hired after December 31, 2020, would raise $101 billion in new revenues for the program over a 10-year period. It would, however, also increase spending over time for those beneficiaries.

Policy Options

Thoughtful health policy reforms can address fiscal concerns, protect Medicare beneficiaries, and enhance efficiency and outcomes in the overall healthcare system.

Allowing Medicare to Negotiate Prices of Prescription Drugs

The United States spends approximately twice the average of other wealthy countries per capita on healthcare, which is partly due to high drug costs. Prior to the enactment of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), Medicare was prohibited from negotiating prescription drug prices directly with manufacturers, which contributed to the government having to pay for medications at relatively higher prices. The IRA authorized the federal government to directly negotiate prices for a limited number of drugs covered by Medicare. Under the enacted provisions, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) negotiated prices for 10 drugs in 2023, with the prices taking effect in 2026. HHS negotiations will determine new prices for an additional 15 drugs in 2027, 15 more in 2028, and finally another 20 drugs in 2029 and after.

Overall, allowing HHS to negotiate drug prices in Medicare is expected to reduce costs for the federal government and for consumers. CBO estimates that all of the provisions related to prescription drugs in the IRA will save the federal government $286 billion over the upcoming decade. Of that, the price negotiating provision is projected to reduce spending by nearly $102 billion over 10 years.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), which passed in 2025, limited the number of drugs that qualify for price negotiation. That change is projected to cost $5 billion over the next decade.

Reducing Federal Healthcare Subsidies

There are a number of available reforms to limit federal healthcare spending. For Medicare, options include modifying payments for Medicare Advantage plans by changing health risk scoring or benchmarking, increasing premiums, passing site-neutral payments, or increasing taxes on benefits, which would reduce the level of financial assistance provided to higher-income beneficiaries. Federal costs could also be limited by imposing caps on spending for Medicaid and subsidies for health insurance. Lawmakers cut Medicaid spending in OBBBA by reforming some pre-existing eligibility requirements in addition to mandating a new community engagement or work requirement.

Changing the Structure of Federal Healthcare Programs

Options that would redesign federal healthcare programs include:

- Combining Medicare’s Part A hospital care program with Part B ambulatory services

- Reforming coverage for low-income individuals who need long-term and high-cost care and are eligible for Medicare and Medicaid (known as "dual eligibles")

- Converting Medicare into a premium support program that would allow beneficiaries to purchase insurance through health insurance exchanges

Additional Social Programs Resources:

- Social Security Administration, Office of the Chief Actuary's Estimates of Proposals to Change the Social Security Program

- Peter G. Peterson Foundation, Social Security Reform: Should We Raise the Retirement Age?

- Peter G. Peterson Foundation, Social Security Reform: Options to Raise Revenues

- Peter G. Peterson Foundation, Social Security Reform: Options to Adjust Benefits

Policy Options