Social Security is the largest program in the federal budget and makes up one-fifth of total federal spending. It provides benefits to nearly 9 out of 10 individuals over the age of 65, or 15 percent of the American population. Without Social Security, research finds that two-thirds of the elderly would be living in poverty.

The program, however, is facing financial shortfalls, and its reserves are currently projected to be depleted by 2033 unless lawmakers take action. At that point, Social Security will not be able to pay full benefits to its beneficiaries. One potential solution for improving the program’s financial outlook is to increase or eliminate the cap on earnings that are subject to Social Security payroll taxes.

What Is the Social Security Payroll Tax?

Federal Insurance Contributions Act (FICA) taxes are the primary source of revenue for Social Security and are the largest component of taxes that are commonly referred to as payroll taxes. Employers and employees each pay 7.65 percent of wages or salary in FICA taxes, split between two social insurance programs. Dedicated Social Security taxes are 6.2 percent and are only levied up to a maximum amount, or income limit, that is determined annually. The other 1.45 percent is dedicated to Medicare’s Hospital Insurance program and is not subject to an earnings cap. Self-employed individuals are also subject to payroll taxes through Self-Employment Contributions Act (SECA) taxes. The rates for SECA taxes are identical to those for FICA taxes, but the self-employed individual is responsible for paying both portions of the tax.

What Is the Social Security Tax Cap?

The limit on annual earnings subject to Social Security taxes is referred to as the taxable maximum or the Social Security tax cap. For 2025, that maximum is set at $176,100, an increase of $7,500 from last year. When the payroll tax dedicated to Social Security was first implemented in 1937, it was capped by statute at the first $3,000 of earnings (which would be equivalent to about $66,800 in 2025 dollars). Since 1975, the taxable maximum has generally been increased each year based on an index of national average wages. About 6 percent of the working population earns more than the taxable maximum.

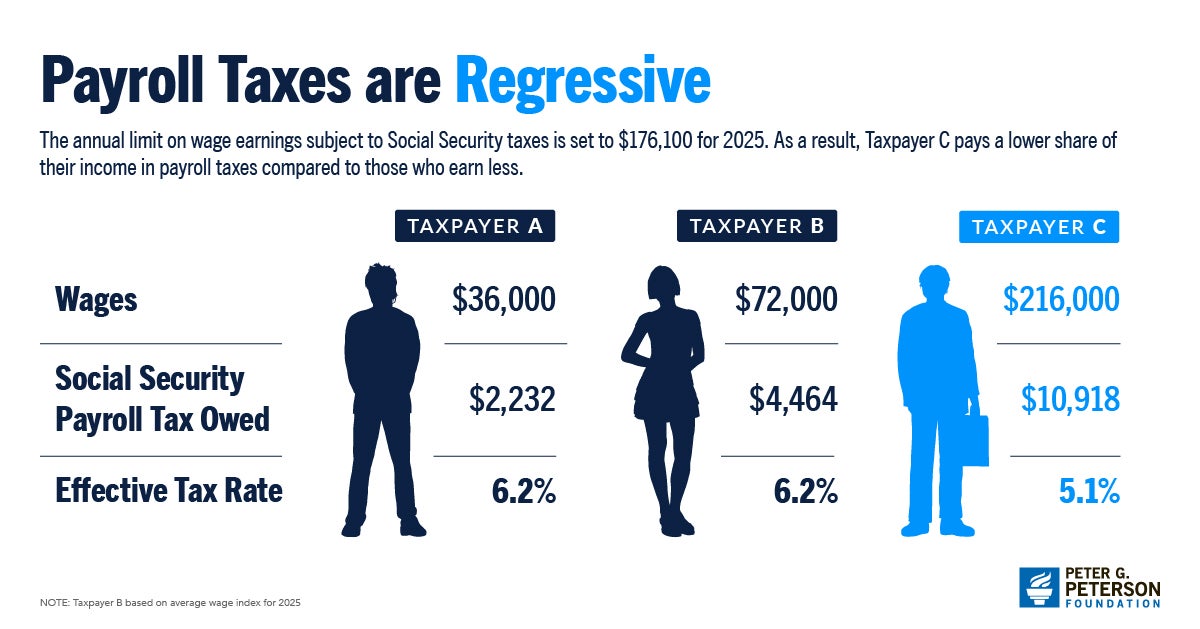

As a whole, the U.S. tax system is progressive, with high-income taxpayers paying a higher effective tax rate. However, payroll taxes are regressive, with low- and moderate-income taxpayers paying a higher share of their income in payroll taxes compared to high-income taxpayers. The regressivity of Social Security taxes is due to the tax cap. For example, someone with average wage income in 2025 of $72,000 per year would owe $4,464 in Social Security taxes. However, someone with triple that income — or $216,000 — would owe $10,918, which is only two and a half times the amount of tax.

What Changes Could Be Made to the Tax Cap?

There have been a number of proposals to increase, eliminate, or otherwise adjust the payroll tax cap as a way to shore up Social Security’s finances. Simply eliminating the tax cap would significantly improve the solvency of the Social Security trust funds, decreasing the programs’ long-range funding shortfall by 73 percent. Providing a Social Security benefit credit for earnings above the current tax cap would eliminate 53 percent of the long-range shortfall.

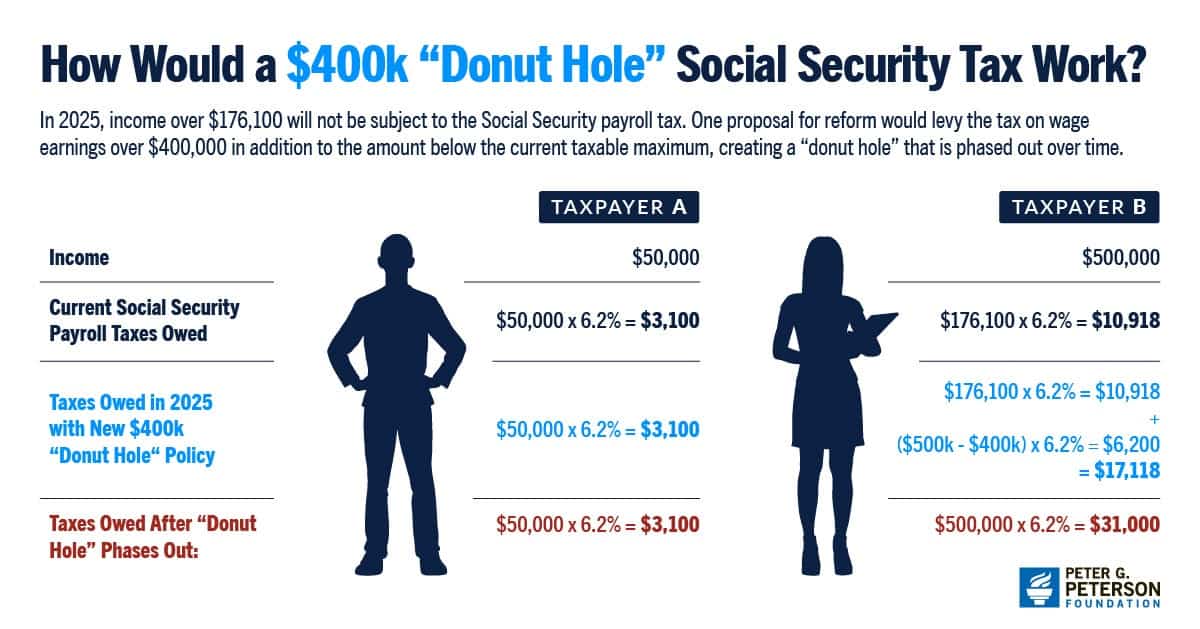

Another proposal would apply the Social Security payroll tax to earnings over $400,000 in addition to earnings below the current maximum taxable amount. The gap between the two would narrow over time as the taxable maximum increases and the $400,000 threshold remains unchanged. The proposed policy design is nicknamed the “donut hole” and would gradually increase the programs’ revenues over time while not subjecting earners who fall in the gap to an immediate tax increase. Adopting a $400,000 “donut hole” policy could eliminate 66 percent of the long-range shortfall.

Another approach that has been proposed by economists is to set the tax cap as a portion of aggregate earnings rather than as a dollar figure. The proportion of total earnings that is subject to the Social Security tax has declined over time because the earnings of the highest-paid individuals have increased more quickly than those of other workers. In 1985, 89 percent of earnings were subject to the Social Security tax, but in 2023 the share had decreased to 83 percent. Adjusting the taxable maximum to 90 percent of earnings would eliminate 24 percent of the long-range shortfall.

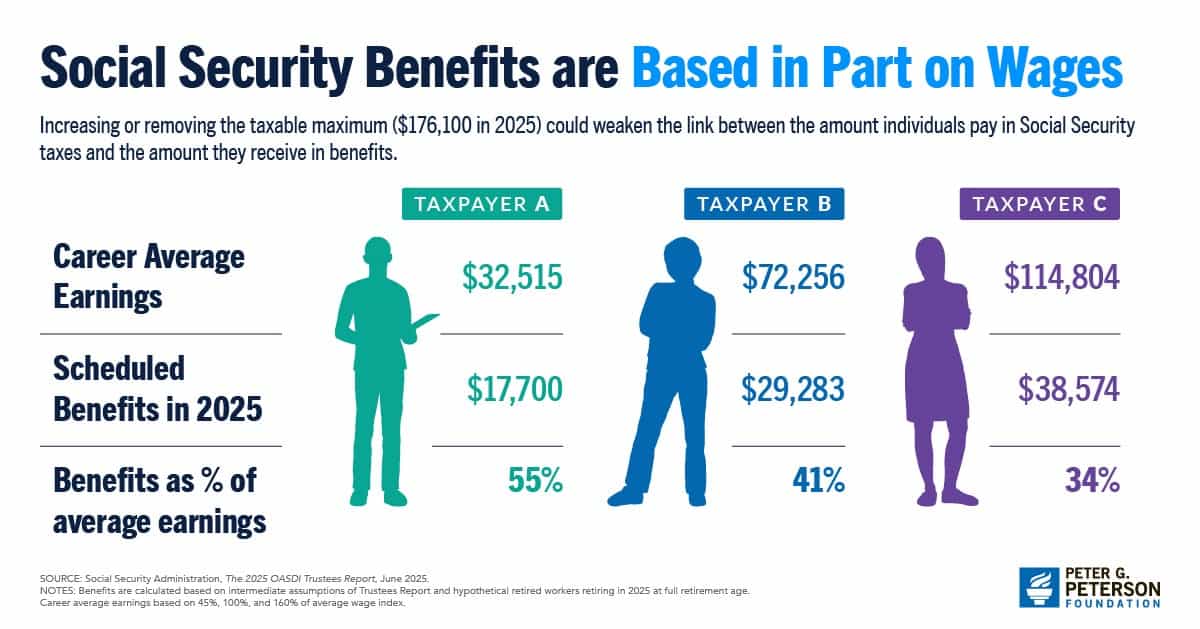

Finally, a consideration when raising or removing the cap on taxable earnings is whether wages above the current cap would also be counted in the formula that determines benefits. Under the current system, an increase in the cap would also raise benefit payments (the maximum, initial monthly benefit for people retiring at age 67 in 2025 is $4,018), thereby leading to higher expenditures for the program (although those would be more than offset by higher tax revenues).

What Are the Pros and Cons of Eliminating the Social Security Tax Cap?

Proponents of increasing or eliminating the limit on earnings argue that it would make the tax less regressive and be part of a solution to strengthen the Social Security trust funds. For example, eliminating the Social Security tax cap while providing benefit credit for additional earnings taxed would delay the insolvency of the Social Security trust funds until 2059, according to the Social Security Administration. Another argument is that removing the taxable maximum would adjust for increasing income inequality and the fact that high-income individuals generally have longer life expectancies. As a result, they receive larger Social Security benefit checks for a greater amount of time.

Opponents argue that increasing or removing the taxable maximum could weaken the link between the amount individuals pay in Social Security taxes and the amount they receive in retirement benefits if benefits are not adjusted upward to reflect tax contributions. Opponents also contend that while low-income earners may pay a greater share of their income to Social Security payroll taxes than high earners, they also receive a disproportionate share of government transfer payments that are not subject to the tax. Those opponents cite programs that have been created to — at least partially — offset the regressive nature of the Social Security payroll tax.

Finally, some economists anticipate that if the limit were lifted, employers and employees might respond by shifting taxable compensation to a form of compensation that is taxed at a lower rate. For example, employers could decrease wages but increase 401k contributions, which are not subject to payroll taxes and are excluded from individual income taxes.

Conclusion

Increasing or eliminating the Social Security tax cap is just one of many solutions for improving Social Security’s financial outlook — but it’s clear that some sort of action must be taken to ensure the future of this vitally important program. More options are detailed here.

Photo by Redgoldwing/Getty

Further Reading

What Are Refundable Tax Credits?

The cost of refundable tax credits has grown over the past several years, with the number and budgetary impact of the credits increasing.

Understanding the New Senior Deduction in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act

The senior deduction adds complexity to the tax code, and fewer than half of seniors will benefit from it.

What Are Estate and Gift Taxes and How Do They Work?

Estate and gift taxes produce relatively lower revenue compared to other sources, but they generate a significant amount of attention, and even controversy.