The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) just released updated budget and economic projections, which highlighted the nation’s unsustainable fiscal outlook. One of the most significant findings from that report is that the federal government’s borrowing costs have increased rapidly over the past year and will grow through the next decade. Most notably:

- Interest payments on the national debt were $475 billion in fiscal year 2022 — the highest dollar amount ever.

- Interest costs grew 35 percent last year and are projected to grow by another 35 percent in 2023.

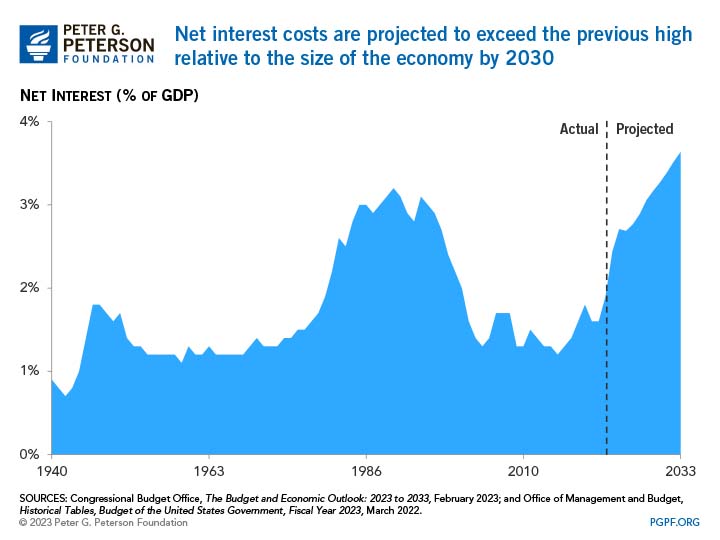

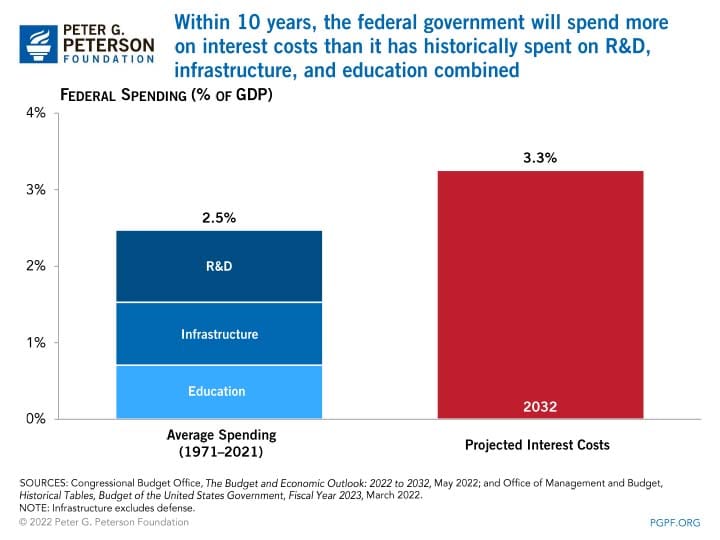

- Relative to the size of the economy, interest costs in 2030 will reach 3.3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), exceeding the previous post-World War II high of 3.2 percent of GDP, which was recorded in 1991.

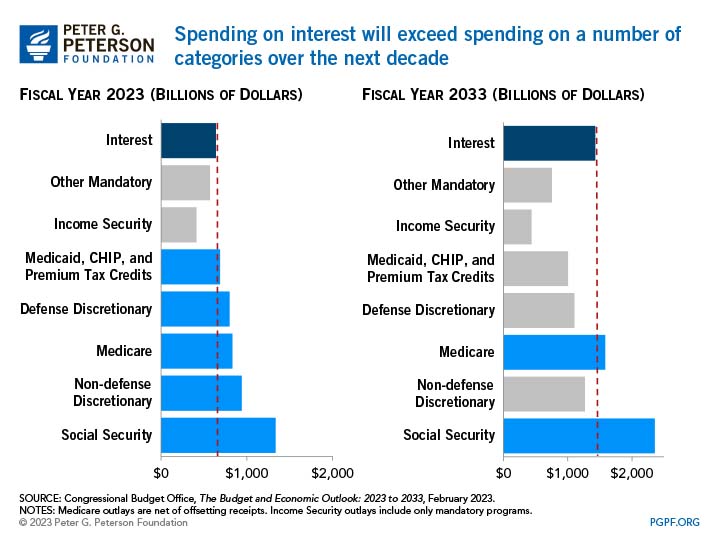

- Within 10 years, net interest costs will exceed federal spending on crucial programs like Medicaid and defense.

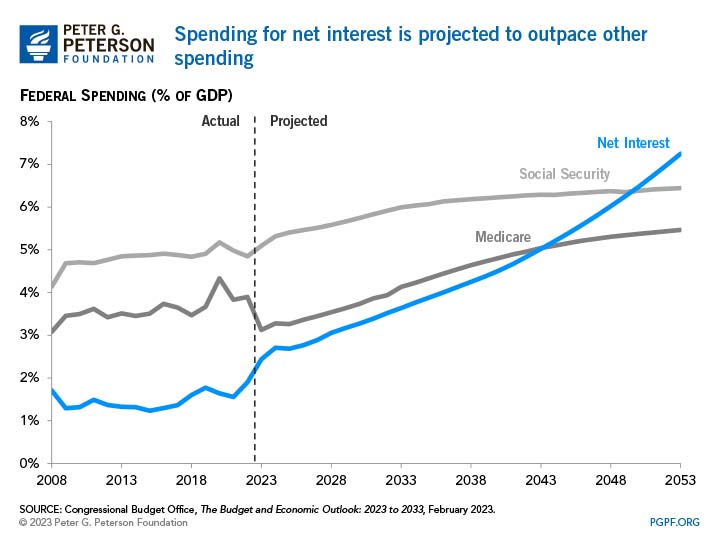

- Spending for net interest will become the largest “program” in the federal budget within the next 30 years, outpacing spending on Medicare and Social Security.

Rising interest payments can crowd out other priorities in the federal budget and lead to a cycle of higher deficits, growing debt, and even more interest payments in the future.

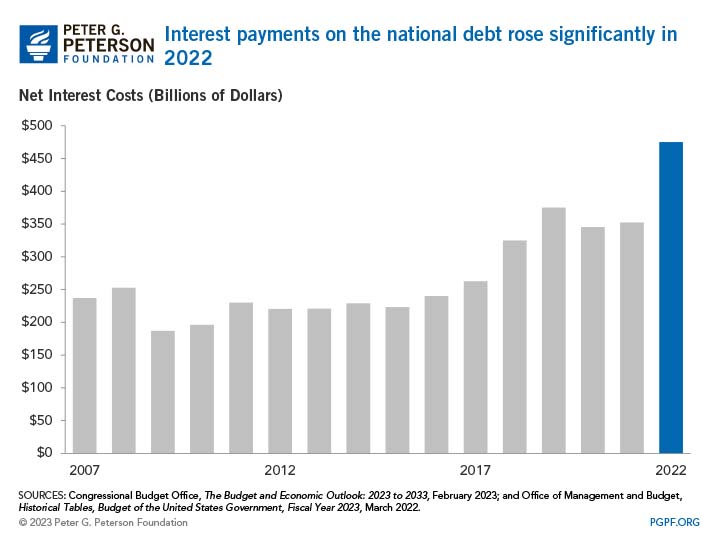

Interest Costs Jumped in 2022 and Will Do So Again This Year

Net interest payments on the national debt rose from $352 billion in 2021 to $475 billion in 2022 — the highest nominal dollar amount in recorded history. Relative to the size of the economy, such costs were 1.9 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), the highest level in 21 years.

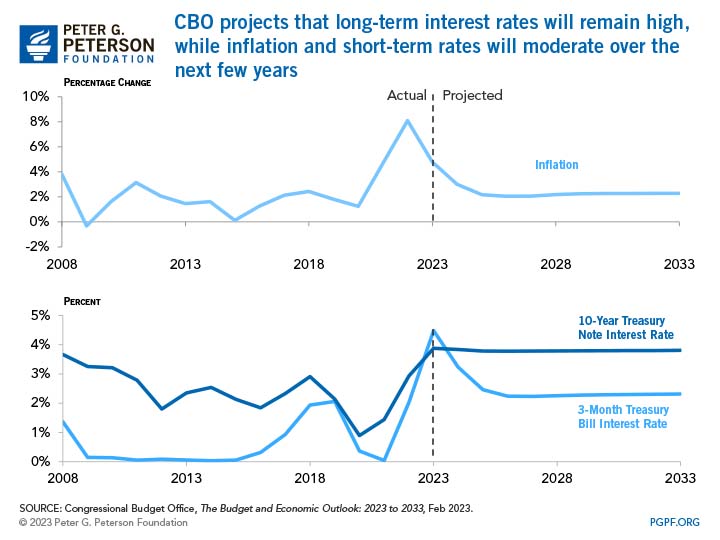

Much of that increase was due to higher interest rates on U.S. Treasury securities. Although borrowing rose sharply over the past few years to address the COVID-19 pandemic, interest costs were muted as a result of low interest rates. However, as inflation rose to a 40-year high in 2022, the Federal Reserve increased the federal funds rate, a monetary policy tool used by the central bank to combat rising prices, seven times in that year. Those rate hikes, in addition to other factors, placed upward pressure on interest rates on U.S. Treasury securities. For example, interest rates on 3-month bills spiked from near zero in 2021 to 2.0 percent in 2022; rates on 10-year notes rose from an average of 1.4 percent in 2021 to 2.9 percent in 2022.

Interest rates on U.S. Treasury securities are expected to continue to rise over fiscal year 2023. Because of that, CBO projects that interest payments on the national debt will increase an additional 35 percent this year, to $640 billion. Those higher payments will contribute to an increase in debt held by the public of 6 percent in 2023.

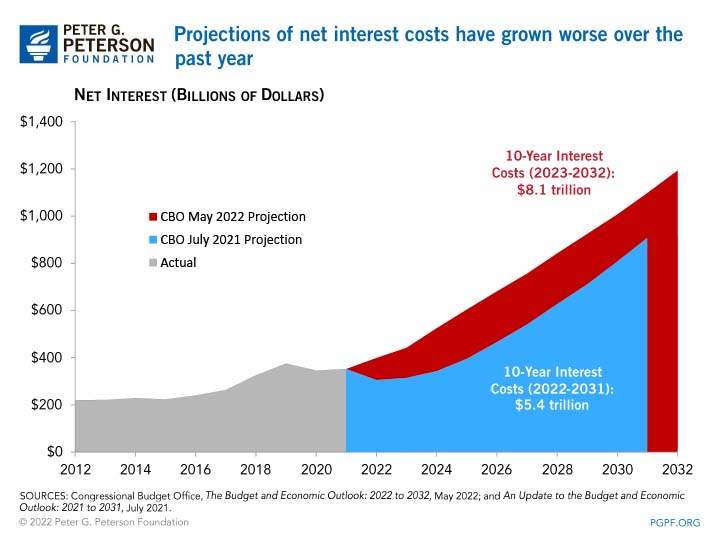

What’s more, CBO projections show a notable increase over what the agency projected in May 2022. Over the 2023–2032 period that CBO reported on last year, they projected that interest costs would total $8.1 trillion. At that time, such a sum was the highest amount over any 10-year total in the past. However, due to high interest rates and debt accumulation, interest costs are now projected to total $10.5 trillion over the upcoming 10 years.

Interest Costs Will Continue Rising throughout the Next Decade

CBO projects that annual interest costs will rise to a staggering $1.4 trillion in 2033. To contextualize that rapid growth, consider that the federal government spent about $1.3 billion per day on interest payments in 2022; by 2033, the nation will spend about $3.9 billion per day. Relative to the size of the economy, such costs would nearly double from 1.9 percent of GDP in 2023 to 3.6 percent in 2033. The previous high for interest relative to GDP in the post-World War II era was 3.2 percent in 1991; that ratio would be exceeded in 2030 under CBO’s calculations.

What’s more, CBO projections show a notable increase over what the agency projected in May 2022. Over the 2023–2032 period that CBO reported on last year, they projected that interest costs would total $8.1 trillion. At that time, such a sum was the highest amount over any 10-year total in the past. However, due to high interest rates and debt accumulation, interest costs are now projected to total $10.5 trillion over the upcoming 10 years.

The Growth in Interest Costs Is Largely Driven by Rising Interest Rates

The level of interest payments on the national debt is mostly determined by the amount of federal debt outstanding and interest rates on U.S. Treasury securities. While the projected increase in borrowing over the next decade will contribute to the rise in the nation’s interest tab, the high levels of interest rates are the primary driver of that rapid growth over the next several years. According to CBO’s projections, the 3-month rate on Treasury bills is expected to rise another half point through the first half of 2023 to around 4.7 percent and then begin to decline. In the second half of the projection period, CBO expects short-term rates to stabilize around 2.3 percent. The 10-year Treasury rate, which currently stands around 3.8 percent, would remain around that level for the rest of the decade.

Interest Costs Will Exceed Other Important Spending Programs within the Next 10 Years

One of the most prominent consequences of high interest payments is that they could crowd out spending on other important priorities within the federal budget. Interest costs represented about 8 percent of total federal outlays in 2022. By 2033, that share will rise to 14 percent and will exceed programs such as defense and Medicaid. At that point, interest payments would be twice the amount the federal government spends on income security programs.

Accruing debt and paying interest over time would be more justifiable if the borrowing were used to make investments. However, very little of the federal budget is allocated to investments such as spending on education, infrastructure, and research and development. In fact, if current policies stay in place, interest costs would exceed what the federal government has historically spent on key investments within the next decade.

Interest Costs Will Become the Largest Program in the Federal Budget within 30 Years

Over the next 30 years, interest costs on the national debt will total around $69 trillion. Relative to the size of the economy, such costs will rise from 2.4 percent of GDP in 2023 to 7.2 percent in 2053 — surpassing Medicare in 2044 and Social Security in 2050.

As interest costs rise, so too will the gap between federal spending and revenues. In fact, CBO projects that interest costs alone will account for 38 percent of federal revenues by 2053, significantly exceeding the level of 10 percent recorded in 2022.

Growth in interest costs in the long term will be driven by an accumulation of federal debt, which is expected to double from nearly 100 percent of GDP in 2022 to 195 percent in 2053, and a sustained, gradual increase in interest rates. Interest rates may remain relatively high, compared to the past several years, in the long run due to a reduction in the Federal Reserve’s holdings of Treasury securities and the continued buildup of the national debt. The escalation in debt puts upward pressure on interest rates and therefore increases interest costs, which in turn further boosts deficits and debt and continues that unfortunate cycle.

Policymakers Need to Act

CBO’s recent set of budget and economic projections make clear our fiscal outlook has deteriorated, driven in large part by a large and growing interest burden. This stark report highlights the need for lawmakers to focus on solutions that break us out of the vicious cycle of borrowing, interest and higher debt - and the good news is there are a range of options on the spending and revenue side.

Image credit: Photo by Douglas Sacha/Getty Images

Further Reading

The Fed Held Its Target Range After Reducing the Short-Term Rate Three Meetings in a Row

High interest rates on U.S. Treasury securities increase the federal government’s borrowing costs.

How Does the United States’ Fiscal Position Compare to Other Countries’?

The United States is in a poor fiscal condition compared to the rest of the world, according to the OECD.

Top 10 Reasons Why the National Debt Matters

At $38 trillion and rising, the national debt threatens America’s economic future. Here are the top ten reasons why the national debt matters.