With narrow majorities in both Houses of Congress, Republicans recently made use of the budget reconciliation process to advance key pieces of their agenda. Reconciliation provides for expedited consideration of certain legislation; its use is particularly important in the Senate because it limits the time allowed for debate and prevents the inclusion of non-budgetary provisions. The reconciliation process avoids the potential need to gather 60 votes to end debate and, therefore, allows the Senate to adopt legislation with a simple majority (51 votes, or 50 votes plus the vice president as tiebreaker).

How Does Budget Reconciliation Work?

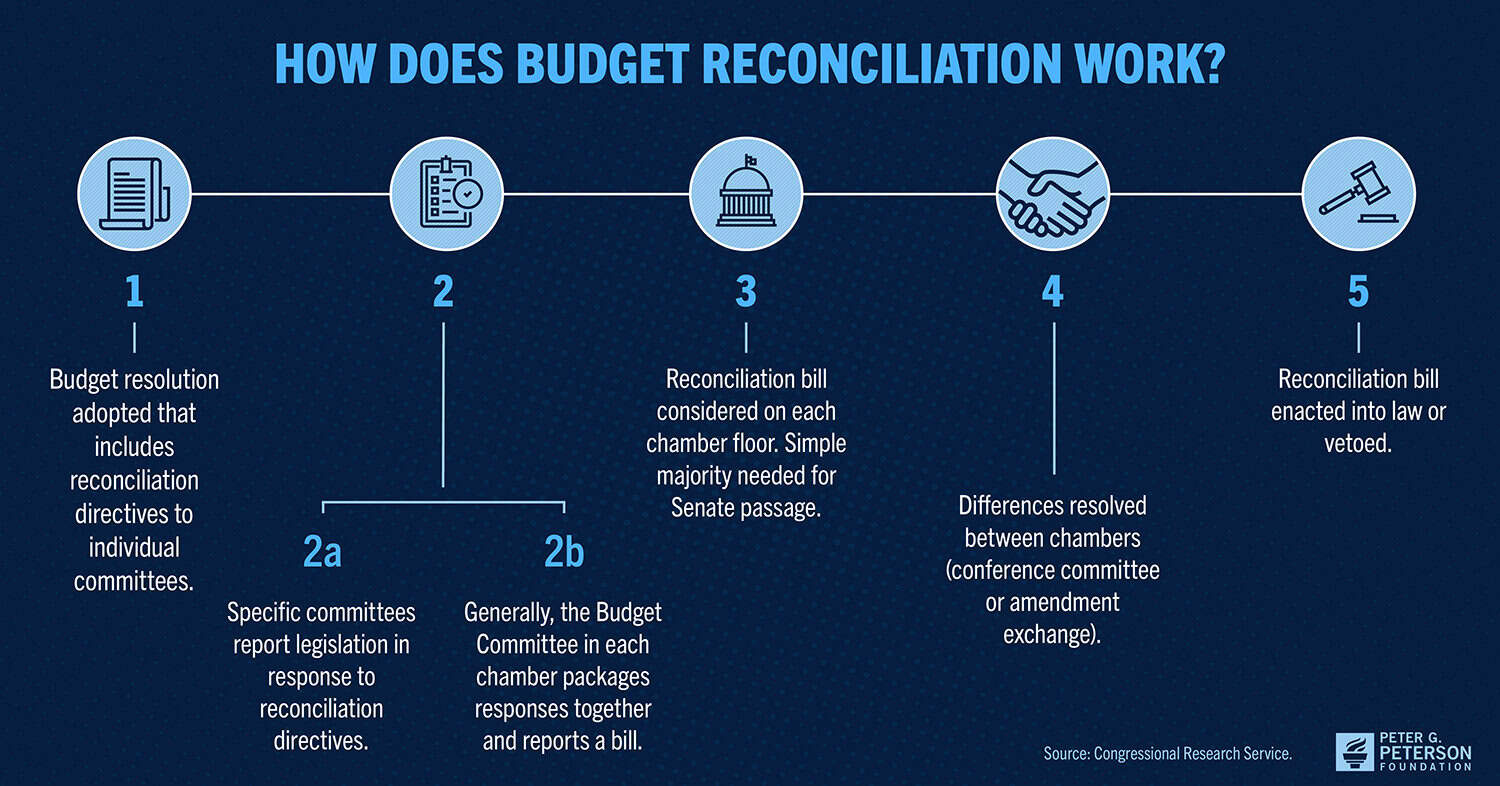

Budget reconciliation is a powerful but complex process that begins when the House and Senate Budget Committees include instructions in their annual budget resolution for other committees to develop and report legislation that has specified effects on mandatory spending, revenues, or the debt limit. If only one committee receives reconciliation instructions, its reported legislation can move directly to the floor for consideration by the full House or Senate. If more than one committee is involved, their legislation is first assembled by the Budget Committees before consideration in each full chamber. In the Senate, because of the limit on time available to debate reconciliation bills, the bill cannot be filibustered to prevent a final vote.

As with all other legislation, if a budget reconciliation bill is passed by the House and Senate, it goes to the president for signature or veto.

What Restrictions Apply to Budget Reconciliation?

The Senate reconciliation bill is subject to the “Byrd Rule,” which limits the types of provisions that can be included in the legislation. Under the Byrd Rule, reconciliation legislation is subject to a point of order on the Senate floor if it contains provisions that violate any one of the six tests. In general, these points of order require 60 votes to waive, thus undermining the Congressional majority’s rationale for using the reconciliation process. Under the Byrd Rule, provisions are subject to a point of order if they meet any one of the following criteria:

- Increase the budget deficit beyond the budget window, which is typically 10 years

- Produce no budgetary effects

- The budgetary effects incidental to the policy change

- Make changes to Social Security

- Produces budgetary effects but was proposed by a Committee otherwise out of compliance with the reconciliation instructions in the budget resolution

- Out of the jurisdiction of the committee proposing the provision

How Frequently Is the Process Used?

Budget reconciliation was established as an option by the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, and it was first used in December 1980. Reconciliation was then used in 20 of the next 45 years. Usually, reconciliation is only used once per year (if it is used at all), but there have been four years — 1982, 1986, 1997, and 2006 — in which Congress passed more than one reconciliation bill. All told, 24 budget reconciliation bills have been enacted into law.

Is Budget Reconciliation Being Used as It Was Originally Intended?

The budget reconciliation process was originally focused on deficit reduction. As the Congressional Research Service notes, “reconciliation has generally been used to reduce the deficit through spending reductions or revenue increases, or a combination of the two.” Congress maintained that focus for the first two decades during which it used reconciliation.

That changed in 2000, when Congress adopted two budget resolutions that called for revenue reductions without any offsetting changes to spending. At the time, senators debated whether it was appropriate to increase the deficit through the reconciliation process. The prevailing interpretation of the Congressional Budget Act of 1974 was that the reconciliation process is neutral when it comes to the deficit — and therefore the budget reconciliation process can increase the deficit. Since then, the Senate has, on several occasions, adopted and repealed rules that prevent deficit increases in the reconciliation process; at present, there is no such rule.

Which Laws Have Been Enacted Using This Process?

Several prominent laws have been enacted using budget reconciliation, with the most recent example being the One Big Beautiful Bill Act (2025), which largely codified the current administration's first iteration of reconciliation, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (2017), while reducing outlays for various social programs. Overall, it significantly increased projected deficits over the 10-year window. Prior to that, budget reconciliation was used to enact the Inflation Reduction Act (2022), which addressed some priorities related to climate change and healthcare.

The reconciliation process was also used in 2010 to pass legislation that created the Affordable Care Act and the College Cost Reduction and Access Act of 2007, which made major changes to federal student loans and established the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program. Other examples of laws that used reconciliation are tax changes in 2001 and 2003 and the reform of welfare programs in 1996.

Has the President Ever Vetoed a Budget Reconciliation Bill?

There have been four instances in which the House and Senate passed a budget reconciliation bill that was ultimately vetoed by the president — once by President Obama and three times by President Clinton. In all four cases, Congress did not override the veto, and the legislation failed to become law.

Budget reconciliation is a powerful tool that lawmakers can use to adjust existing laws to guide the nation’s fiscal path. Reconciliation has been employed in times of narrow political majorities and as a practical workaround to enact controversial policies that otherwise would not make it through the legislative process. Regardless of which budget processes are used, lawmakers need to exhibit sound decision-making to preserve our most important programs and safeguard our fiscal future.

Photo by Samuel Corum/Getty Images

Further Reading

Lawmakers are Running Out of Time to Fix Social Security

Without reform, Social Security could be depleted as early as 2032, with automatic cuts for beneficiaries.

Budget Basics: How Does Social Security Work?

Social Security is the largest single program in the federal budget and typically makes up one-fifth of total federal spending.

How Did the One Big Beautiful Bill Act Affect Federal Spending?

Overall, the OBBBA adds significantly to the nation’s debt, but the act contains net spending cuts that lessen that impact.