A key component of the ongoing negotiations surrounding the Administration’s “Build Back Better” legislation is whether and how policymakers will pay for their priorities. In its budget for 2022 released in May this year, the Biden Administration originally proposed a number of changes to the tax code to raise revenues to fund its priorities — most notably an increase in the statutory corporate income tax rate from its current level of 21 percent to 28 percent. More recently, the president has signaled a willingness to raise the rate to 25 percent.

The possibility of raising the corporate tax rate has spurred a debate among economists and policymakers about the optimal corporate income tax rate to balance revenue generation and U.S. competitiveness. In general, proponents of increasing the corporate income tax rate argue that doing so would help ensure corporations pay their fair share, bring such revenues back in line with historical norms, raise new revenues to pay for national priorities and improve our fiscal outlook, and help address inequality. Advocates who push for a lower corporate rate argue that raising the cost of capital stifles investment in the economy, reduces productivity, and inhibits the private sector as an engine of growth.

In this piece, we will examine the history of the statutory corporate income tax rate and analyze aspects of the contemporary debate.

How Has the Corporate Income Tax Evolved over Time?

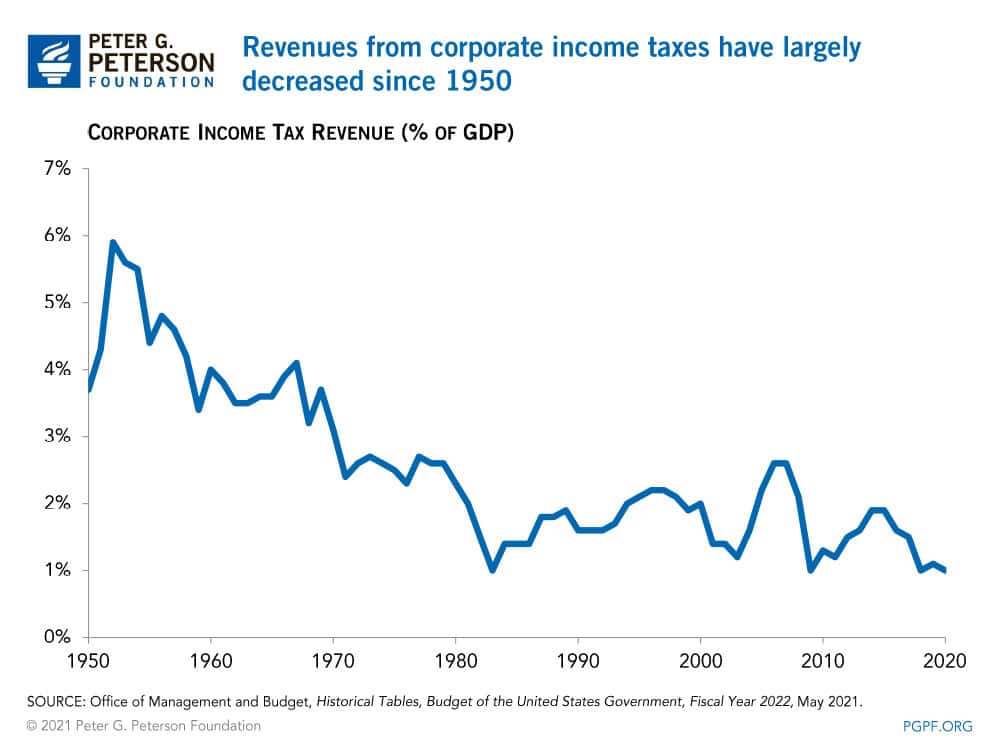

The statutory corporate income tax rate has fluctuated considerably since its enactment in the Corporate Tax Act of 1909, which established a 1 percent tax on all business income over $5,000. By 1934, the rate had increased to 13.75 percent on all business income, generating 12 percent of federal tax revenues (and measuring 0.6 percent of gross domestic product, or GDP). The rate jumped considerably during the 1940s and 1950s due to federal wartime expenses and the succeeding recovery period, averaging 44 percent between 1940 and 1959; over that time, revenues from the corporate income tax accounted for an annual average of 28 percent of federal revenues and 4.4 percent of GDP.

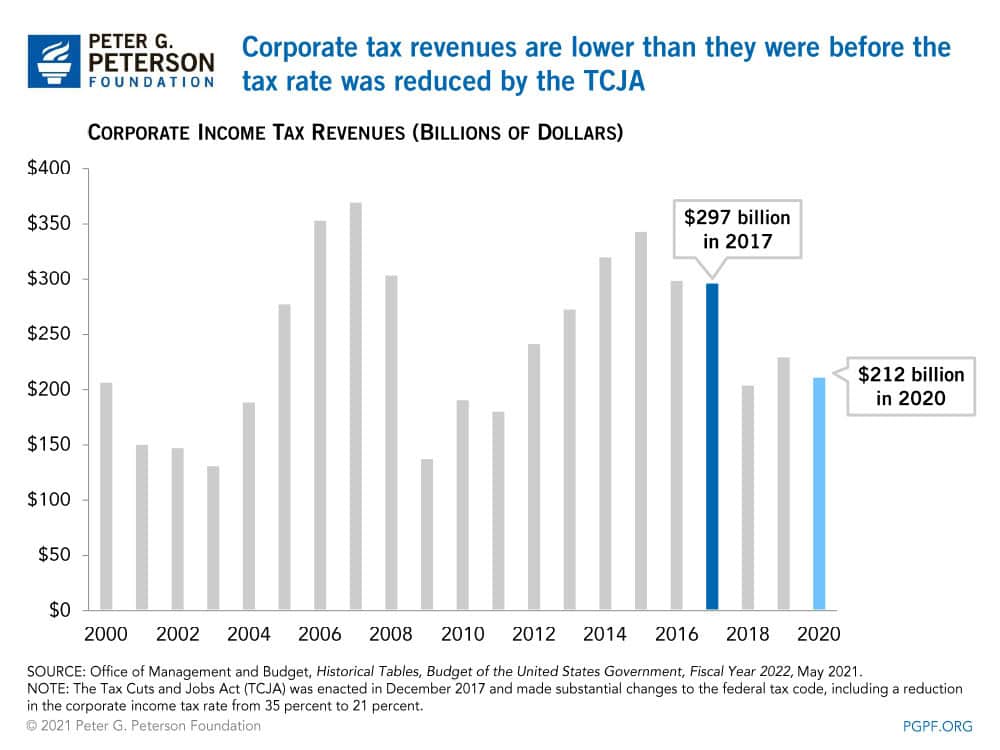

The corporate income tax rate reached a peak of 52.8 percent in 1968 and 1969 before steadily dropping to around 35 percent in 1993, where it remained until 2017. In December 2017, President Trump signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) into law, which, among other provisions, slashed the corporate tax rate to 21 percent, the lowest it had been since 1939. As a result, revenues generated from that source dropped by about 30 percent in 2018 and have represented less than 10 percent of federal revenues (or roughly 1 percent of GDP) every year since the TCJA was enacted.

Arguments in Favor of Increasing the Corporate Tax Rate

In a press release accompanying President Biden’s initial infrastructure plan, the White House proposed increasing the corporate tax rate from 21 percent to 28 percent to help offset the package’s costs. The Administration estimates that doing so would return corporate income tax levels to pre-TCJA levels relative to GDP while still maintaining a tax rate 7 percentage points lower than the rate in place between 1980 and 2017. Although the Administration does not provide exact revenue estimates for a 28 percent corporate income tax rate, it does state that “raising the corporate income tax rate would modestly increase corporate revenues relative to GDP, still leaving them below those of our trading partners.” The White House also projects that a 28 percent corporate rate would raise enough new revenues to “help fund critical investments in infrastructure, clean energy, research and development, and more to maintain the competitiveness of the United States and grow the economy.” Lastly, the Administration believes that “raising the corporate income tax would help attenuate inequality,” since the corporate tax is a relatively progressive component of the U.S. tax system.

Similarly, an analysis from economist Bill Gale in his book Fiscal Therapy argues in favor of a 25 percent corporate income tax rate, along with several other amendments to the corporate tax system such as eliminating special preferences for non-corporate businesses and changing the tax to apply to cash flows rather than profits. Gale estimates that increasing the statutory rate to 25 percent, coupled with expensing all investment and eliminating interest deductions, could reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio by 12 percentage points by 2050 (current projections show that debt will reach 195 percent of GDP by 2050).

Many proponents of increasing the corporate tax rate also note that the TCJA’s substantial reduction to the rate to 21 percent in 2017 did not yield a boom in investment and economic output, which had been a core argument in favor of the legislation. According to data from the Center for American Progress (CAP), corporations in 2018 diverted much of their newfound tax savings to shareholders as opposed to growth-stimulating investment activity like capital expenditures and research and development. Even prior to enactment of the TCJA, many experts noted that corporations held near-record amounts of cash and did not face liquidity constraints that would stand in the way of investment, regardless of changes to the corporate tax rate. CAP argues that corporations would need to boost necessary investments in order for corporate tax cuts to have any of the long-term trickle-down effects championed by proponents.

Arguments Against Increasing the Corporate Tax Rate

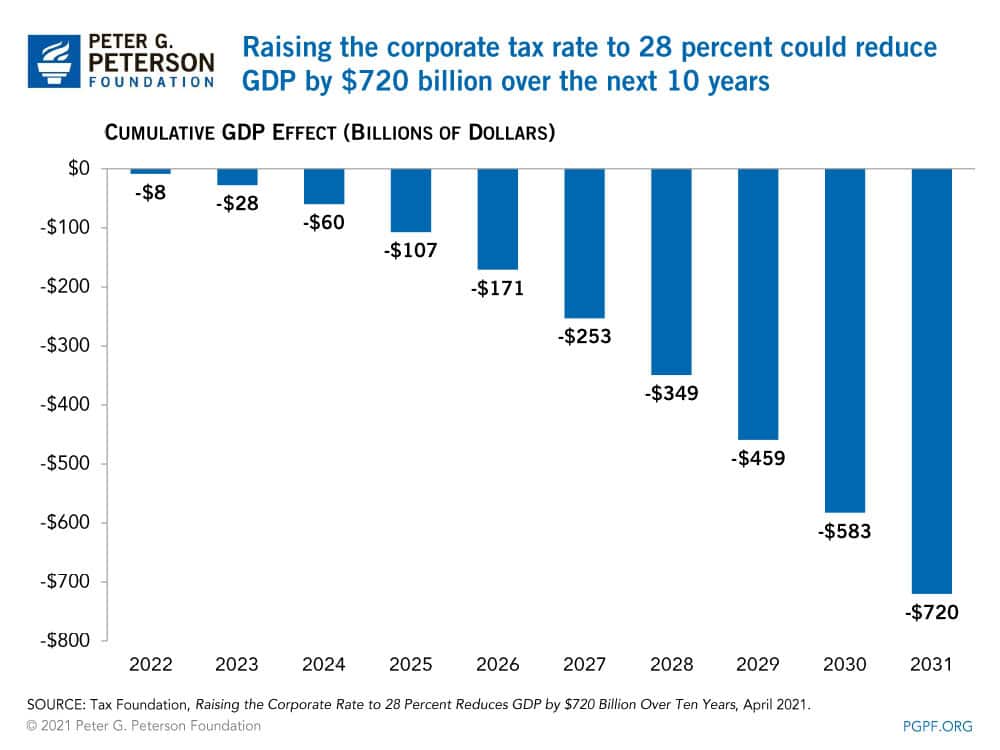

Although raising the corporate income tax rate to either 25 or 28 percent would boost federal revenues, some economists worry such increases could have negative impacts on the economy and U.S. competitiveness. For example, an analysis from the Tax Foundation estimates that an increase in the corporate income tax rate to 28 percent would reduce GDP by a total of $720 billion between 2022 and 2031, based on an assumption that a higher corporate tax raises a company’s cost of capital, ultimately reducing investment and economic growth.

The Tax Foundation also argues that a higher statutory corporate rate would reduce capital investment by corporations in the future because a higher tax would decrease their net earnings. In this scenario, “a higher corporate income tax reduces long-term productivity growth,” which in turn can depress wages. For that reason, the analysis goes on to say, “a significant portion of the economic cost of the corporate income tax falls on workers.” The Tax Foundation projects a 1.5 percent decrease in after-tax incomes for the bottom quintile of earners and a 1.4 percent decline for middle-quintile earners. A similar analysis from the National Association of Manufacturers analyzing the effects of a 25 percent corporate tax rate found that real wages would fall by 0.5 percent, while employment would drop by 500,000 annually.

Another argument against a corporate tax hike is the potential to undermine American competitiveness in the global economy. According to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, raising the corporate rate to 28 percent would give the United States the highest combined corporate income tax rate (i.e. the federal rate plus state and local rates) among the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries. The Chamber of Commerce argues that such a high rate would make the United States a less attractive place to invest profits and establish corporate headquarters, diverting much-needed capital and jobs away. Specifically, the Chamber projects that raising the corporate rate to 28 percent would cause the United States to drop from 21st to 30th in global competitiveness, which is even lower than the pre-TCJA level.

Conclusion

It remains to be seen whether lawmakers will pass an increase to the corporate income tax rate to raise revenues to help pay for new federal spending. As the legislative process continues to unfold, the debate surrounding the merits and pitfalls of revising the corporate tax is likely to take center stage as lawmakers seek to pay for their priorities.

Image credit: Isaac Lee/Getty Images

Further Reading

The United States Collects Less Tax Revenue Than Other G7 Countries

The U.S. collects less tax revenues compared with other G7 countries, and that lower level of revenues is a key driver of the national debt.

Energy Tax Policy Under the OBBBA

As part of the OBBBA, lawmakers rolled back existing energy tax incentives in order to partially offset the bill’s deficit impact.

The Six Largest Corporate Tax Expenditures

Relative to the size of the economy, the U.S. collects less revenues than many other advanced countries. Tax breaks are a contributing reason.