The lawmakers we choose this November will face critical fiscal and economic decisions in the near future. Next year, the President and the Congress will confront a series of urgent deadlines, including how to address the debt ceiling and what to do about major elements of the tax code. Policymakers will also soon be facing decisions about how to deal with the shortfalls in the two largest programs in the federal budget — Social Security and Medicare.

As voters look ahead to the November election here are some of the major fiscal deadlines and decisions that the leaders we elect for the next two, four, and six years will face.

Debt Ceiling Reinstated (January 1, 2025)

In early 2023, the federal government hit its debt limit, also known as the debt ceiling, at which point the Department of the Treasury used a variety of accounting maneuvers known as “extraordinary measures” to temporarily keep the government from defaulting on its debt. In June 2023, policymakers enacted the Fiscal Responsibility Act, which included a suspension of the debt limit.

The debt ceiling will be reinstated on January 1, 2025, just days before the swearing in of the 119th Congress and weeks before inauguration. At that point, if the ceiling has not yet been addressed, the Treasury will have to immediately resume extraordinary measures and policymakers will once again have to come together to find a solution. If lawmakers don’t come to an agreement by the time that extraordinary measures lapse, the federal government may be at risk of defaulting on its debt. Even a short-term breach in the debt limit could have significant economic implications — reducing gross domestic product, wiping out trillions of dollars in U.S. household wealth, and resulting in the loss of millions of jobs.

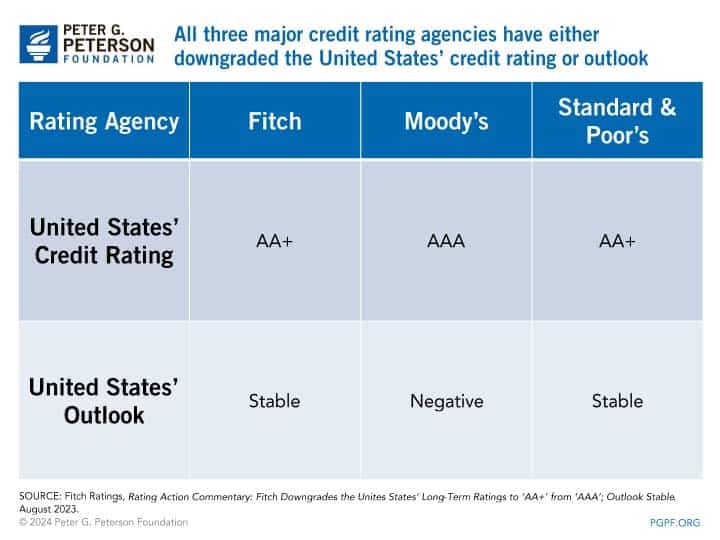

Moreover, waiting until the last minute to resolve the debt ceiling could have negative consequences. While the federal government has never defaulted on its debt, the last-minute fiscal brinkmanship on the debt ceiling is a periodic source of anxiety for financial markets and has incited worries about the government’s creditworthiness in the past — threatening the U.S. credit rating, increasing interest rates, and causing measurable damage to the economy. In fact, all three major credit rating agencies have either downgraded the nation’s rating or the nation’s rating outlook in recent years:

- In 2011, when Congress delayed addressing the debt ceiling until the last minute, Standard & Poor’s lowered the sovereign credit rating for the United States, citing the brinkmanship over the debt limit as one of the reasons.

- In August 2023, just two months after the nation’s most recent debt limit impasse, Fitch Ratings downgraded the U.S. credit rating due to the erosion of good governance in addition to the nation’s unsustainable fiscal outlook and lack of a plan to address that outlook.

- In November 2023, Moody’s Investors Service lowered its outlook for the U.S. credit rating from “stable” to “negative,” which signals an increased risk in the country’s top rating being downgraded over the next couple of years, due to debt affordability and political polarization over issues such as the debt limit.

The new year will start off with one of the most important, and consequential, decisions for policymakers. Elected officials should work together to address the debt ceiling in a way that doesn’t harm the U.S. economy and improves the nation’s fiscal trajectory.

Discretionary Spending Caps Expire (September 30, 2025)

The Fiscal Responsibility Act also instituted limits on discretionary spending for fiscal years 2024 and 2025. At the end of the 2025 fiscal year, those caps will expire, and lawmakers will have to agree on the amount of appropriations for the following fiscal year. Failure to come to an agreement on annual appropriations could result in a shutdown of some government activities.

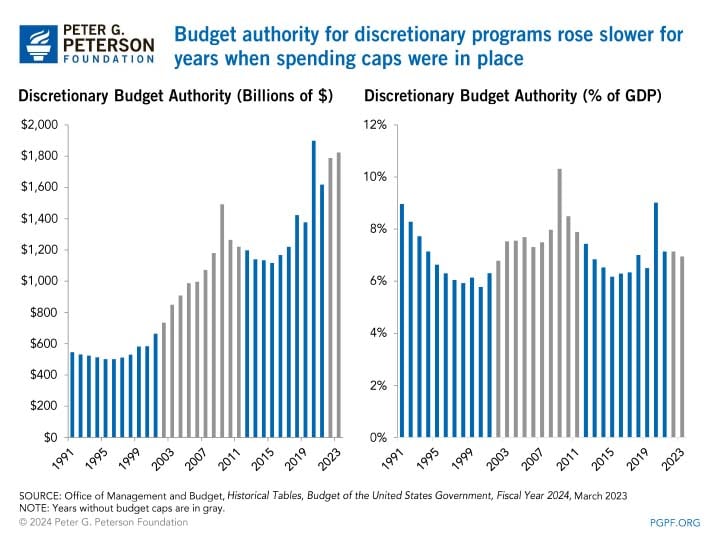

While evidence suggests that spending caps have been somewhat effective at reducing discretionary spending in the past, their efficacy is undermined when lawmakers weaken, remove, or otherwise circumvent them. Overall, in periods with budget caps in place, discretionary budget authority grew at a slower pace year to year compared to times without caps. The average year-over-year growth rate for periods with caps (1991–2001 and 2012–2021) was 3 times less than it was for the years without caps (2002–2008).

While discretionary spending is not the leading driver of the debt, it is a major part of the federal budget, and placing budget caps on discretionary spending is potentially one element of a fiscally responsible package to address the country’s long-term budgetary path.

The Expiration of Major Tax Provisions from the TCJA (December 31, 2025)

In 2017, lawmakers enacted the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), which significantly changed the way individual and corporate income is taxed under the federal tax code. While most of the changes to the corporate tax code were legislated to be permanent law, such as the reduction of the top corporate tax rate from 35 to 21 percent, many of the changes made to individual income tax provisions, as well as certain other provisions, are slated to expire at the end of 2025, including:

- Lowering tax rates and altering tax brackets for individuals and families

- Increasing the standard deduction

- Doubling the Child Tax Credit and increasing the phase-out threshold

- Placing a cap on the State and Local Tax (SALT) deduction

- Creating a new "pass-through” deduction for households with income from certain businesses

- Raising the exemption amount for the alternative minimum tax and increasing the phase-out income threshold

The TCJA included a wide range of provisions, many of which could be defensible or worthy of consideration as part of a fiscally responsible tax-reform package. However, taken as a whole, it is undeniable that the TCJA made the country’s fiscal outlook worse, and extending its provisions without offsetting the cost would make the debt trajectory even more daunting. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), extending all provisions of the TCJA that are set to expire in 2025 would increase federal deficits by $4.6 trillion over the 2025–2034 period (including net interest costs). As 2025 approaches, policymakers should consider a package of tax reform that makes the system more efficient and does not make the fiscal situation worse.

Enhanced Subsidies for the purchase of Health Insurance expire(December 31, 2025)

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was signed into law in 2010 in an attempt to lower healthcare costs and expand healthcare coverage for millions of Americans. To that end, the ACA established marketplaces to facilitate the purchase of health insurance from competitive markets, and it provides tax credits to individuals who purchase health insurance through those marketplaces, commonly referred to as premium tax credits. Eligibility for those premium tax credits has generally been limited to individuals with income less than 400 percent of the federal poverty line. However, policymakers made a couple of temporary changes to such credits as part of the American Rescue Plan of 2021. Those changes were expanded through subsequent legislation and are now set to expire at the end of 2025:

- Waiving the income limit for eligibility to receive the premium tax credit

- Increasing the amount of the tax credit

Permanently extending those provisions would add $383 billion to federal deficits over the next 10 years, according to CBO. However, the premium tax credits are a relatively small portion of federal healthcare spending, making up about 6 percent of such spending in 2024. Nevertheless, the premium subsidies play a significant role in providing healthcare to those who would otherwise be unable to afford it and are a contributing factor to the decline in the uninsured population of more than 10 million people over the past decade.

The extension of subsidies for people buying their own health coverage through marketplaces will run out in 2025, and the next Congress will need to decide whether any of the more generous support should be extended and, if so, how to pay for it.

Depletion of Social Security's Retirement Trust Fund (2033)

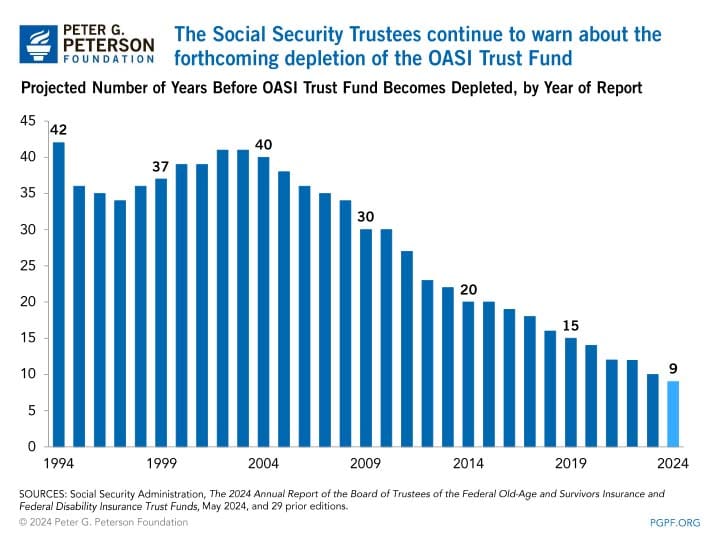

Social Security is a vital program for millions of Americans, making up around 30 percent of income for retired individuals and helping millions avoid poverty. Without reform, Social Security’s Old-Age and Survivor’s Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund will be depleted in just 9 years — the closest it has ever been to depletion since reforms in 1983 — and will be unable to pay out full benefits. Upon trust fund exhaustion in 2033, the benefits paid out through the program would only be equal to the amount of revenues coming in, meaning 70 million beneficiaries would incur an automatic cut of 21 percent to their retirement benefits at that point — an average of about $16,500 for a typical couple.

The financial shortfall facing the OASI Trust Fund is largely caused by an aging population. The number of workers contributing to the program is growing more slowly than the number of beneficiaries receiving monthly payments. In 1964, there were 4.0 workers per beneficiary; that ratio has dropped to 2.7 today and will continue to fall in the future.

While it may seem as though ample time exists, the Senators elected this year will be serving through 2030, just three years before Social Security will be depleted. There are a number of policy solutions to shore up this important program, and if lawmakers act soon to address the trust fund shortfalls, they will be able to phase in changes gradually and responsibly in a way that does not harm vulnerable populations.

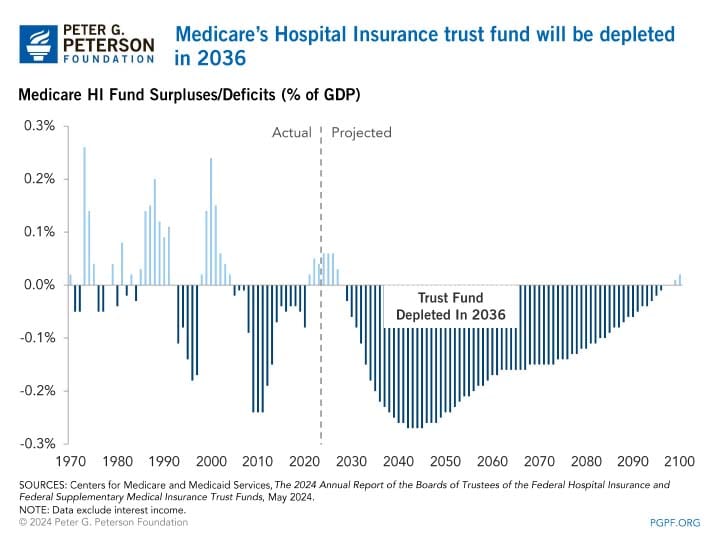

Depletion of Medicare's Hospital Insurance Trust Fund (2036)

The Hospital Insurance (HI) Trust Fund, which finances hospital care for Medicare, is also on unsound financial footing. Rising healthcare costs and an aging population are driving Medicare costs. As the nation’s population ages, enrollment in Medicare will continue to climb as older Americans spend more on healthcare, on average, than do younger Americans. The combination of the long-term trend of rapid healthcare cost growth and population aging accelerates HI spending, which is projected to climb from 1.5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2024 to 1.9 percent in 2036.

Unless policymakers take action, Medicare’s HI Trust Fund would be depleted in only 12 years, at which point payments to medical providers would be automatically cut by 11 percent.

Policymakers must put the Nation on a Sustainable Fiscal Trajectory

The lawmakers we choose this November will face a number of crucial decisions that have enormous consequences for the nation’s fiscal and economic outlook. Debt is already rising at an unsustainable pace — in their latest projections, CBO estimated that the federal debt will grow from 97 percent of GDP in 2024 to 166 percent in 2054. What’s more, the interest payments on that borrowing are accumulating rapidly and will soon reach record highs — no matter how you measure it. With all of these critical decisions and deadlines looming, the 2024 election is a fiscal election.

Photo by Samuel Corum/ Getty Images

Further Reading

Lawmakers are Running Out of Time to Fix Social Security

Without reform, Social Security could be depleted as early as 2032, with automatic cuts for beneficiaries.

What Is the National Debt Costing Us?

Programs that millions of Americans depend on and care about may be feeling a squeeze from interest costs on our high and rising national debt.

Interest Costs on the National Debt Are Reaching All-Time Highs

The most recent CBO projections confirm once again that America’s fiscal outlook is on an unsustainable path — increasingly driven by higher interest costs.