You are here

The Financial Condition of Social Security

Overview

The Social Security Trustees report—which was delayed by more than 3 months— factors in the impacts of the new health care reform law on the long-term balance of the Social Security Trust Fund. The report reveals that Social Security is in a precarious financial position in both the short and long term.

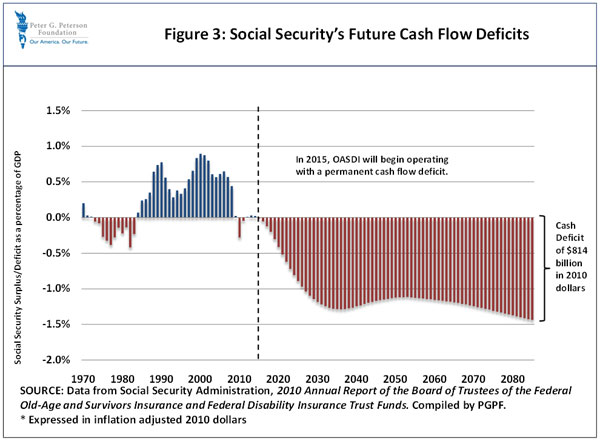

- In the short term, Social Security will operate with cash flow deficits in 2010 and 2011. This means that the cost of benefits in 2010 and 2011 are greater than the amount of income generated by payroll taxes earmarked for Social Security benefits. As the economy recovers, Social Security is expected to briefly return to a cash flow surplus in 2012 but will begin to run a permanent cash flow deficit in 2015.

- In the long term, the Social Security Trust Funds are estimated to be completely exhausted in 2037. Absent reform, once the Trust Fund is exhausted, Social Security will only be able to pay approximately 78 percent of scheduled benefits. Click here for a discussion on trust funds.

- The unfunded promises to the nearly 53 million current beneficiaries and all workers currently paying payroll taxes into the Social Security program are estimated to be $5.4 trillion.

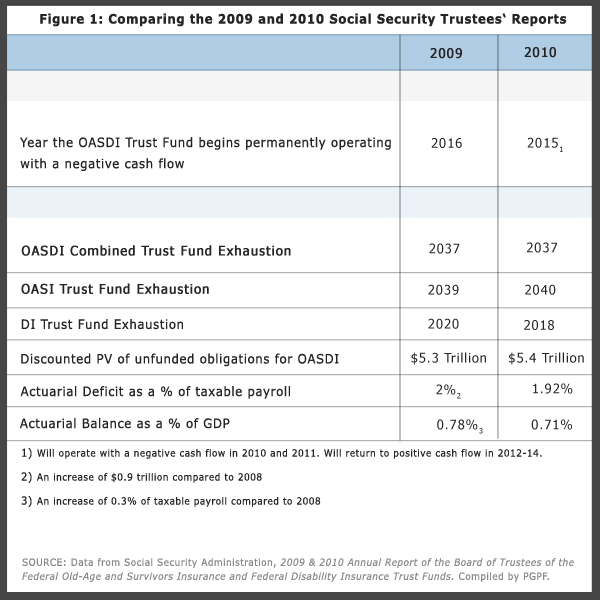

While the Trustees report focuses on the financial condition of Social Security as a single isolated program, the financial condition of Social Security has important implications for the overall Federal budget. As a federal program, Social Security cannot be any stronger financially than the overall federal government, and looming financial problems in Social Security will have a negative impact on the Federal budget as a whole. As the program’s financial condition continues to deteriorate, providing full benefits will lead to higher deficits and require increased Federal borrowing from the public, absent policy reform. Figure 1 provides a side-by-side comparison of the financial condition of Social Security from the 2009 and 2010 Trustees Reports.

Social Security’s Unsustainable Financial Outlook

The Social Security Trustees’ report includes several measures to evaluate Social Security’s financial health. All of these indicate that over the long term, the cost of Social Security’s benefit costs will be greater than the resources available to finance them. As the financial condition of Social Security deteriorates, the pressure that this program places on the rest of the budget will continue to increase. Reforms are required to sustain the program for future retirees and to relieve mounting pressure on the budget as a whole.

|

Reforming Social Security— Why we can’t afford to wait: There is a high cost for delaying necessary reforms to Social Security. In a recent report CBO analyzed 30 policy options that have been considered to make Social Security sustainable in the long run. In this report CBO created different time lines for two options to illustrate how much delaying reform will cost. The first option would gradually raise the payroll tax over the two decades. The second option would reduce benefits to new beneficiaries. In the case of increasing payroll taxes, reform resulting in the ability to pay full scheduled benefits through 2083 would require an increase in the payroll tax of 2 percentage points over 20 years if the reform begins in 2012. If reform was delayed until 2022, a 2 percentage point increase would only extend full scheduled benefit payments through 2056. To pay full scheduled benefits through 2083 with a ten-year delay, it would be necessary to raise the payroll tax by 2.6 percentage points. The second option evaluated the effect of a flat 15 percent reduction in benefits paid to new beneficiaries beginning in 2017. This reduction would extend Trust Fund solvency until 2076. If reform was delayed until 2027, a 15 percent benefit cut would only extend solvency until 2044. To achieve solvency through 2076 benefits would need to be cut by 20 percent in 2027. |

||

| Source: Congressional Budget Office, Social Security Policy Options. July, 2010. | ||

The long term, unsustainable financial outlook for Social Security results from the aging of the population, which results from increasing longevity, stable fertility rates, and the retirement of large numbers of the baby boomers. The Trustees Report projects that the number of workers per beneficiary will decline from a current ratio of about 3 workers per beneficiary to 2.1 by 2035.

Policy makers have a number of options to choose from to improve Social Security’s long-term condition. However, such reforms are time sensitive (see Box 1). The longer policy makers wait to implement reform, the larger the adjustments to benefits and payroll taxes will have to be to achieve financial sustainability.

Measuring Social Security’s Financial Condition and the Federal Budget

Social Security is largely a pay-as-you go program—current workers’ payroll taxes pay for the benefits of retirees and other beneficiaries. Two government accounts—the Old Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) program and the Federal Disability Insurance (DI) program, keep track of the program revenues and expenses. The Trustees Reports analyze the condition of these accounts. Reforms enacted in 1983 increased worker contributions and gradually raised the full retirement age. As a result of those changes, Social Security has generated substantial interest-earning surpluses. As a result, by the end of 2009, trust fund balances had grown to approximately $2.5 trillion.

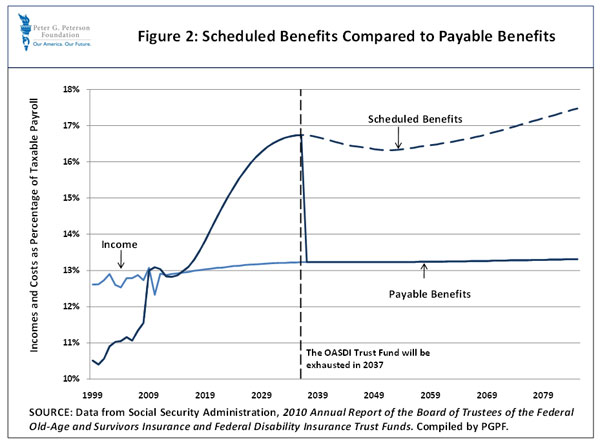

The accumulated balances in the trust fund accounts represent future legal authority for benefits. According to the 2010 Report, the program has sufficient resources to pay for scheduled benefits until 2037, when the funds will be exhausted. Absent a change in current law, once all available resources are exhausted Social Security will only be able to cover 78 cents of every dollar of scheduled benefits (see Figure 2). This will deteriorate to about 75 cents per scheduled dollar of benefits by the end of the 75 year projection period.

Cash Surpluses and Deficits

The Trustees report also provides projections of Social Security’s cash transactions. From 1983 and 2009, Social Security ran cash surpluses. Those surpluses reduced the federal government’s overall budget deficits and the amount it had to borrow from the public. It is not possible to know what would have happed to the federal budget if Social Security had not run surpluses. The government could have borrowed more from the public, federal spending for other programs could have been lower, or taxes might have been higher.

The updated projections show that the Social Security Trust Fund will run temporary cash deficits in 2010 and 2011. This reflects the poor condition of the economy. People are retiring earlier, and more are collecting disability benefits after the financial crisis. Lower employment levels have reduced the income stream flowing into the Trust Fund from payroll taxes. As the economic recovery begins to take hold, small cash surpluses should return between 2012 and 2014. This brief period of surpluses will end in 2015 and Social Security will begin to operate with a permanent negative cash flow (see Figure 3).

As Social Security’s cash flow turns negative, overall budget deficits and Treasury borrowing from the public could increase, which, in turn, could increase pressure on policy makers to reduce spending in other programs or to raise taxes to continue paying full scheduled benefits.

Actuarial Deficits

Another measure of Social Security’s financial condition is its actuarial deficit. The actuarial deficit is the difference between the projected income and costs of Social Security expressed as a percentage of taxable payroll. This measure represents how much income must be increased or costs must be reduced for each of the next 75 years to bring Social Security’s income in line with the cost of maintaining current level benefits. The actuarial deficit over the 75-year period is currently 1.92 percent of taxable payroll, (0.08 percent of taxable payroll lower than the 2009 estimate). Closing this deficit all at once would require an immediate and permanent 12 percent reduction of benefits, an immediate and permanent payroll tax increase equivalent to 1.84 percentage points, an immediate transfer of $5.4 trillion from general revenues, or an approach that combines these three options.

Conclusion

Social Security is in an unsustainable financial position in the short and long term. In the short term, Social Security is operating with a cash flow deficit. The program will briefly return to cash flow surpluses in 2012, but in 2015 the program will begin to operate with a permanent cash flow deficit. In the long term, the cost of providing benefits will permanently exceed program revenues, and the program will no longer be able to pay full benefits starting in 2037. Demographic change is the primary driver of this financial outlook. Without reform, Social Security will place an increasing strain on the federal budget as a whole as the need for more federal borrowing to provide benefits will be required and deficits continues to swell. Waiting until 2037 would precipitate sharp changes in the budget and could result in jarring adjustments to Social Security. Financial preparation for retirement is a long-term activity Social Security reforms need to begin soon to make changes more gradual and to allow people time to adjust their retirement plans.