You are here

What are Caps on Discretionary Spending and Do They Work?

As part of the legislation to suspend the debt ceiling, lawmakers have once again instituted limits on discretionary spending. Some lawmakers argue that capping such spending will help rein in deficits and stabilize the nation’s fiscal outlook. Let’s look at the trends in discretionary spending and how effective caps are in reducing the debt.

What Are Discretionary Spending Caps?

Discretionary spending refers to programs that are subject to the annual appropriation process, as opposed to mandatory spending, which refers to programs governed by permanent law. More than three decades ago, lawmakers first introduced caps on discretionary spending, which place limits on subcategories of such funding. Typical subcategories divide total appropriations into defense and nondefense buckets.

Recent History of Discretionary Spending Caps

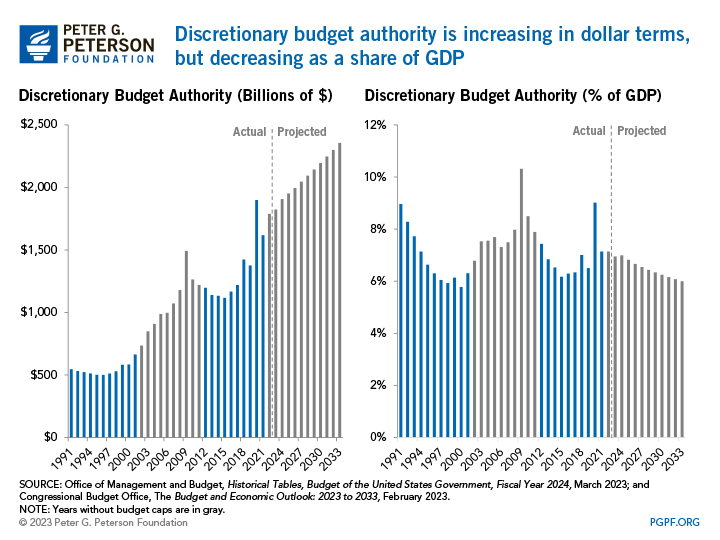

Over the last three decades, discretionary spending has risen in terms of dollars but actually has fallen relative to the size of the economy. In 1991, discretionary spending totaled 8.8 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), but had declined to 6.7 percent by 2022. Discretionary caps were in place for approximately two-thirds of that time period, suggesting that they contributed in restraining growth — at least during certain time periods.

In addition to caps, another factor that likely contributed to the decline in discretionary spending relative to GDP was the “peace dividend,” where U.S. defense spending fell after the demolition of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Funding for defense dropped from 5.5 percent of GDP in 1991 to 3.3 percent just five years later.

Though the overall trend was a decline in discretionary spending relative to the economy, there were some years that disrupted that trend. Notably, more funds were allocated to support the country during extreme emergencies, such as the financial crisis that began in 2008. That drove an increase in discretionary spending from 2009 to 2011, in which Congress allotted almost $500 billion in emergency funding over those years as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. A similar approach was taken in response to the COVID-19 pandemic where $694 billion in emergency discretionary funding was provided from 2020 to 2021.

What Is the Origin of Budget Caps and What Is Their Status Now?

In 1990, the Budget Enforcement Act (BEA) first established caps on discretionary spending (and also created enforcement mechanisms on other components of the budget) to help restrain appropriations and reduce the budget deficit. The caps set out in the BEA covered three categories: defense, international, and domestic spending (but later used just defense and nondefense as categories). If the limits on any of those categories were exceeded, the BEA provided an enforcement mechanism, known as sequestration, whereby the President would be required to cancel resources and bring total funding back to the cap levels. The caps were initially set to expire in 1995 but were extended and redefined in 1993 and 1997. However, the 1990s represented a time of economic growth and budget surpluses were achieved at the end of the decade as tax revenues ballooned. As a result, interest in enforcing the caps waned, and they were allowed to expire in 2002, even though budget deficits had returned by that year.

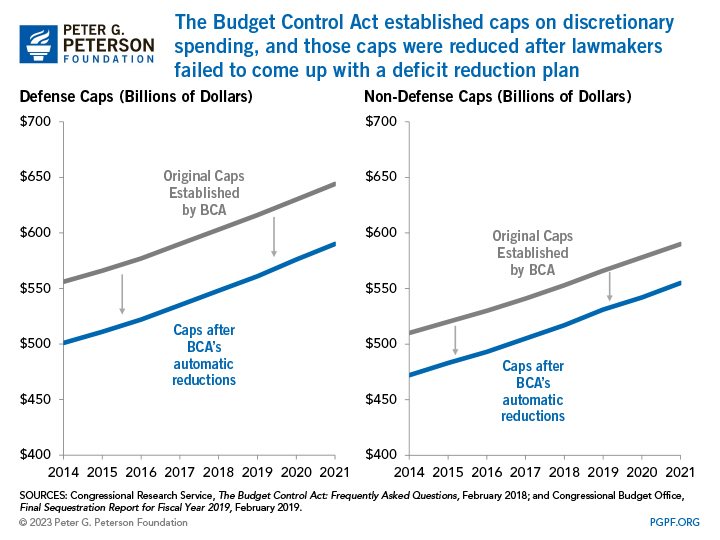

Subsequently, the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA) implemented caps from 2012–2021 as part of a deal to avert what was known as the “fiscal cliff.” The BCA also established a committee to develop a proposal that would reduce the deficit by $1.5 trillion over a 10-year period. When that committee failed to come up with a plan, the BCA’s contingency for deficit reduction went into effect, creating automatic spending reductions of $1.2 trillion. Most of those automatic spending reductions were applied to defense and nondefense discretionary programs, thereby reducing the limits on appropriations below the amounts set in the BCA.

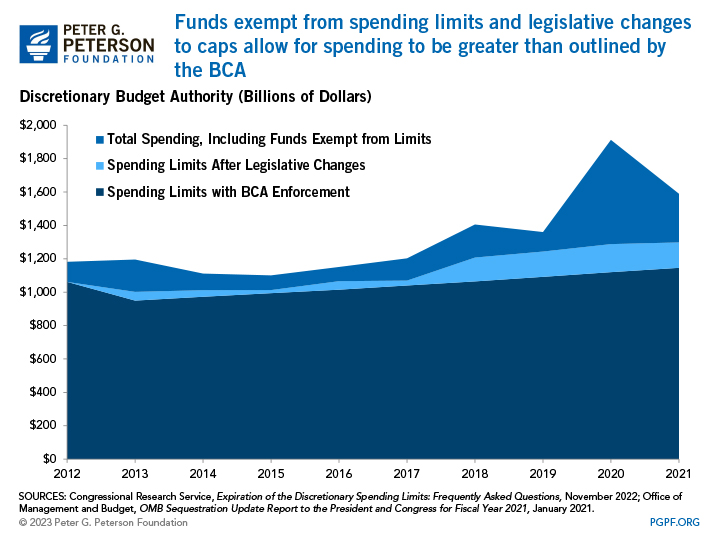

However, not all discretionary programs were constrained by the caps. Funds deemed “emergency spending” were exempt, and in addition, certain other categories were considered outside of the caps:

- Overseas Contingency Operations, which consists mainly of funding for activities in Afghanistan and similar missions

- Disaster relief and beginning in 2020, activities related to wildfire suppression

- Program integrity initiatives, which are intended to reduce overpayments in benefit programs

While the Budget Control Act was in effect, multiple pieces of legislation subsequently raised existing spending limits (the Bipartisan Budget Acts of 2013, 2015, 2018, and 2019), and the provision for caps expired completely at the end of fiscal year 2021.

Discretionary spending had no caps in place for 2022 and 2023, but the recent passage of the Fiscal Responsibility Act will reinstate caps for fiscal years 2024 and 2025. Discretionary budget authority will be capped at $1.59 trillion in 2024 and $1.61 trillion in 2025, but the caps will expire thereafter.

Have Spending Caps Been Effective at Reducing Discretionary Spending?

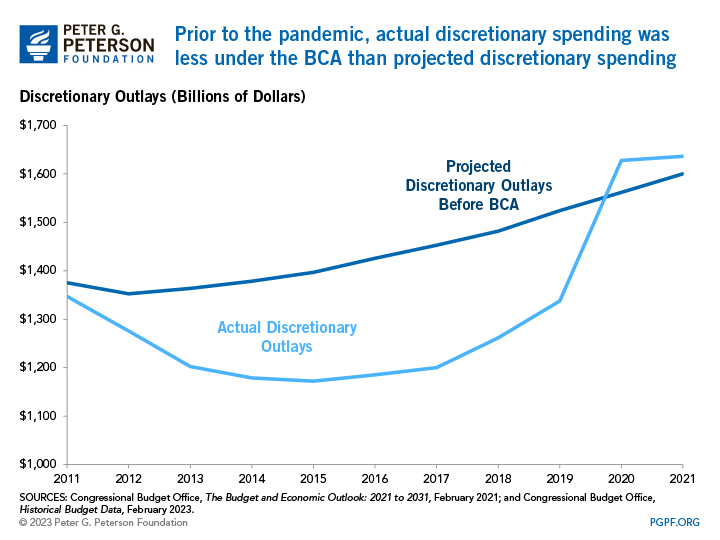

Evidence suggests that budget caps were somewhat effective at reducing discretionary spending, and, unsurprisingly, their impact was lessened when lawmakers weakened, removed, or otherwise circumvented them.

Overall, in periods with budget caps in place, discretionary budget authority grew at a slower pace year to year compared to times without caps. The average year-over-year growth rate for time periods with caps (1991–2001 and 2012–2021) was 2.8 percent and 3.7 percent, respectively, whereas the years without caps before the financial crisis (2002–2008) averaged 8.6 percent. Furthermore, discretionary outlays for years under the BCA were lower than pre-BCA projected levels. Discretionary outlays from 2012 to 2021 averaged 9 percent less than CBO’s projections before the BCA went into effect.

However, in almost every year with caps in place, lawmakers used advance appropriations, obligation delays, timing shifts, and other funding devices to increase discretionary spending above the limits. From 2013 to 2021, annual adjustments to the caps on budget authority averaged $90 billion. Additionally, funds deemed emergency spending were not subject to spending limits, which meant that funding could increase even further beyond the legislated cap increases. That explains the spikes in discretionary budget authority in 2009 and 2020 when emergency funds were enacted to stimulate economic recovery as a response to the 2008 financial crisis and COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, lawmakers enacted an additional $624 billion in emergency spending on top of the original $1.1 trillion budget cap in order to mitigate the economic challenges of the pandemic.

Conclusion

Discretionary caps are only as effective at reining in spending as lawmakers are committed to enforcing them. They are an available tool for lawmakers to address one key area of the budget, but it’s also important to remember that discretionary spending is not a key driver of the country’s total debt. With rising costs of government programs, major trust funds headed toward depletion, and record debt levels, budget caps on discretionary spending are potentially one element of a fiscally responsible package to address the country’s long-term budgetary path.

Related: What’s the Difference between a Government Shutdown and the Debt Limit?

Image credit: Photo by dkfielding/Getty Images